Introduction: rather like my previous Novaxia vs Bigpharmia post, this is an attempt to archive various bits of Twitter threads, as a hopefully more permanent back up in case Twitter’s own copies should disappear.

This all dates back to the spring of 2021. Schools were open again, children were being encouraged to lateral flow test twice a week, but there were a lot of arguments about the effect of false positives at low prevalence.

For example, this article in the Guardian quoted some pretty pessimistic figures for PPV (positive predictive value: the proportion of positive tests that were correct)

As of today, someone who gets a positive LFD result in (say) London has at best a 25% chance of it being a true positive, but if it is a self-reported test potentially as low as 10% (on an optimistic assumption about specificity) or as low as 2% (on a more pessimistic assumption).

The issue here was not really a mathematical one: given the figures for the false positive rate, true positive rate and prevalence, everyone would agree on the PPV value, which can be calculated using Bayes’ Theorem. The issue was more to do with what numbers should be plugged in to the formula. Obviously if only 1 in 50 positive tests were actually correct, then that would be a huge problem, and call into question the value of the whole testing programme.

So here are a couple of pieces of the jigsaw, which arose from slightly unconventional data sources.

Orkney and Shetland lateral flow tests

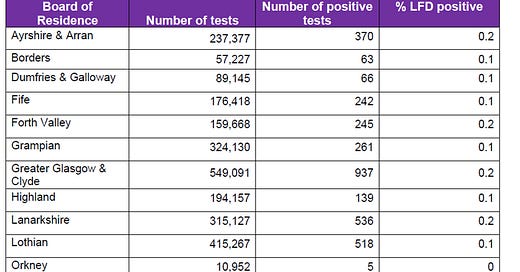

I realised that there were weekly reports of lateral flow test outcomes published in Scotland, broken down by region. See for example here the report of 14th April 2021 which set me thinking about this, and the figures given on page 25.

As I described in this Twitter thread of 18th April, we could look at the really low levels of positive tests in Orkney and Shetland. For example, there had been 4 positive tests out of 15,383. So even if all of them were false positives then that would suggest a false positive rate of 0.026%. (If any of them were true positives then the implied false positive rate would be lower, but this figure was already really low - much lower than many people assumed at the time).

You could even go further and work out a confidence interval based on these numbers. I kept this up for a number of weeks, and the sample size got bigger, but the overall estimate remained pretty consistent.

I think the final version was this one, which implied that

even if all of the 13 out of 53,656 positives so far had been false, that's a false positive rate of 0.024% (CI 0.014%-0.042%)

The interesting thing for me was that this estimate of around 0.03% matched the value of the ‘best statistical fit’ found by more official UKHSA estimates, based on some clever arguments to do with retesting positives with a PCR test, but realising that PCR tests aren’t perfect either - so some ‘lateral flow positive, PCR negative’ samples could actually be true positives.

PCR retests added to dashboard

Somewhat in the spirit of this UKHSA analysis, we were suddenly presented with a real-world version of this data. On 9th April 2021, the dashboard was updated to remove positive lateral flow tests which had failed PCR retesting:

Further, we had dates when these cancelled tests had been taken, so by just looking at March, when prevalence had been low we could deduce that

14,149 verified LFDs, and adding up today's "daily change" figures for March gives 3,191 cases taken off, so 18.4% of +ves false

In other words, the positive predictive value, even at that low prevalence, was 82%. Not the 2% from the Guardian, and based on real-world data not modelling assumptions. In my view, it was still worth performing routine PCR confirmation at that level of PPV, but overall, the chances were that a positive lateral flow test was correct.

This somewhat ad hoc analysis was followed up by the BBC, including a quote from me

"This suggests that people who test positive using a lateral flow device should definitely take that result seriously, and isolate while waiting for a follow-up PCR test," said Prof Oliver Johnson, director of the institute for statistical science at the University of Bristol.

"The fact that a high proportion of these rapid tests have been confirmed by the slower PCR method means that they can be a valuable tool in controlling the pandemic."

Partly as a result of all of this, faith in lateral flow tests generally grew to the stage where the Guardian now referred to them in more glowing terms:

Of course, part of that was due to the general rise in prevalence compared with March 2021, due to the arrival of delta and omicron, as well as relaxation of lockdown restrictions. Indeed, by tracking the weekly PPV values, it was possible to get a sense check on the reported prevalence figures - and this helped identify the Immensa issue of autumn 2021.

Excellent