One small step for man

Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way

I don’t normally take requests, but someone asked me an interesting question on Twitter the other day. There was a news story about recent improvements to Dijkstra’s algorithm for finding efficient routes through networks, which was referred to as the most significant progress for 41 years.

In response, Charles Arthur pointed out what this says about the human spirit:

What amazes me about this is the colossal amounts of failure implied here. So many other people have tried and failed to better Dijkstra. But these folks said "maybe this time?" enough times with enough determination to make it work.

So much hidden effort lies beneath the world.

He then went on to ask me about it

If I were suggesting things I'd be interested to read your Substack take on, it would be how mathematicians pick themselves up after what must be failure after failure on work like this. Is that why it's the younger ones who do stuff? Less beaten down?

To be honest, I’d never really thought about it that way! I don’t personally go to bed each night feeling beaten down and despairing because I haven’t proved the Riemann Hypothesis that day (or not for that reason anyway), but I think it’s interesting to think about why.

I may not be the best person to ask about this, of course. Charles is a big tennis fan, so to put it in that language: you are asking the guy who once won a challenger tournament in Kazakhstan how Carlos Alcaraz felt when he lost the Wimbledon final. I’m (probably) a member of the same species as Terence Tao, and theoretically I’m in the same business, but we’re operating on an entirely different level. But still, I do feel qualified to talk a little bit about mathematical failure.

I recently put a new paper on the arxiv about how probabilities behave on networks, and on some level, what I wrote on LinkedIn about it is true:

For at least 25 years, it has bothered me that binomial distributions don't behave the way that you think that they should.

It’s probably something that’s been at the back of my mind for that period, in a “something doesn’t feel right here” kind of way. But it’s certainly not been the case that I’ve sat down each day and tried unsuccessfully to make sense of it - that would indeed represent a dispiriting pattern of failure.

In the intervening 25 years I’ve worked on a bunch of other problems. I’ve managed to get far enough with some of them to write a paper that a journal would publish. Many of them have been entirely unrelated to this itch that I wanted to scratch, but some have been somewhat related. But for long periods of time, this problem has been locked away somewhere in the back of my mind, waiting for a good idea or a new angle.

And in this case, I started thinking about these matters in a new way after I had a trip to speak at a conference at Yale in 2024, and heard a talk which set me off again. I happened to have a PhD student coming on board around then, and we started working on things related to this problem together. But it was never explicitly a goal to figure out the specific thing that I mentioned, we just wanted to understand the general area better, and the fact we ended up making sense of the issue that bothered me was a pleasant bonus.

Of course, back on the Kazakhstan challenger thing, this is a very long way from the Riemann Hypothesis. It’s not even a problem that people had formulated and written down as such. But even on the very rare occasions that I did solve an unsolved problem with a name, it was probably 10-15 years after I first heard the question, but I certainly didn’t spend the entire intervening period thinking about it.

However, there’s an obvious counterexample to the way that I am describing my own process of mathematical research. When proving Fermat’s Last Theorem, Andrew Wiles famously did lock himself away for seven years before emerging triumphantly with a solution. So maybe that’s the difference? Maybe if I did have the time and the headspace to single-mindedly think about nothing else for a decade, perhaps I too could be at Wiles’s level?

I’m not convinced that’s true, but that’s partly because this story doesn’t entirely capture what Wiles set out to do. As you might know, Fermat had famously claimed that, unlike the fact that 16+9=25, it is impossible to find two cubic numbers which add up to a cube, two fourth powers which add up to a fourth power, and so on. Hearing that, it’s tempting to imagine that Wiles was just sitting and multiplying numbers together for seven years and trying to spot a pattern. In fact the reality was very different.

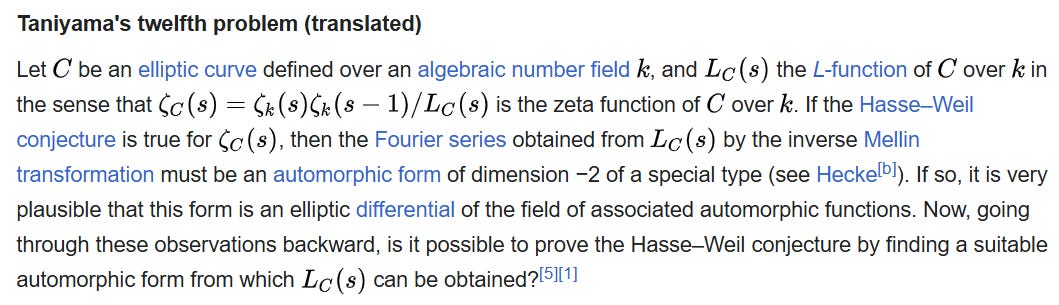

There’s a sense in which Wiles wasn’t playing with numbers at all. In fact, the problem that he was working on was a version of this, first stated by the Japanese mathematician Taniyama in 1955:

I’m not expecting you to know what these words mean! You’d probably need to take a few graduate courses in number theory to even understand the question. And it’s certainly not obvious how Taniyama’s very abstract problem relates to Fermat’s very concrete one.

I think the best analogy is to think about a series of stepping stones that may or may not allow you to reach an island in the middle of a lake. The island is Fermat, and a sequence of mathematicians, including Frey, Serre and Ribet had started to build a plausible-looking path of stones towards it. In particular, they had shown that if there was a way to jump to the Taniyama mini-island, then there was a route through to the big Fermat island itself.

So in that sense, while brilliant, Wiles wasn’t acting in isolation. He wasn’t working entirely outside the scope of the mathematical community, he was relating the famous problem to things he knew, and hoping that the methods that he had would be enough to get there. Even if he didn’t prove Fermat itself, it was likely that his ideas and results would be of value, either to help someone else reach that island, or to be of interest in their own right.

In the same way, I’d imagine that someone working in a cancer lab doesn’t go to work every day feeling “I must cure cancer”, but rather they are hoping to finish their experiments on what some chemical pathway in some particular cell structure might reveal.

This is partly why I am sceptical that the current wave of AI tech bros trying to solve Millennium Maths Problems will get anywhere directly. If I take my favourite LLM and ask it to solve the Riemann Hypothesis, I’m essentially asking it to take a single leap to that island in one go.

To me, it’s more likely that progress will be made by at least understanding the previous efforts. For example, my Bristol colleague David Platt has shown by computer that if something strange happens then it happens for very large numbers indeed. There’s an intriguing potential link between the problem and the equations of quantum mechanics. Perhaps that’s the beginning of a path of stepping stones we can follow, perhaps it’s a dead end.

But the people who are working to establish this connection know that, whether or not they solve the whole problem, then they are finding interesting things, ruling possibilities in or out, and so on. Which hopefully answers Charles’s question about whether the life of a mathematician is inevitably a life of despair and disappointment - though don’t expect such a positive answer at the end of an unsuccessful research morning!

Love the subhead, too.

The stepping stones analogy for mathematical progress is spot-on. The Fermat-Taniyama connection wasn't obvious at all, yet it became the critical path. That's precisley why the "just ask AI to solve the Riemann Hypothesis" approach misses what actually happens in research: building smaller bridges between known territories rather than impossible leaps. Dunno if younger mathematicians really have more stamina or just less awareness of how hard these things are.