This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

More than three years from the start of the coronavirus pandemic and nearly six months since Elon Musk spent $44 billion on Twitter, it feels like a good time to talk about how things end.

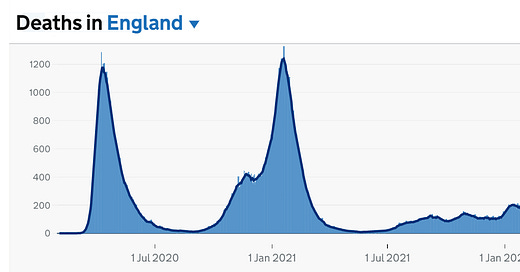

Back in the summers of 2020 and 2021, it was possible to be optimistic about the trajectory of COVID. Deaths in England had fallen exponentially from their peak, and we were down to perhaps ten per day, 99% or so down from their maximum. In 2021 in particular, we’d vaccinated a large proportion of the most vulnerable population. It felt like it wouldn’t take long for infections and jabs to fill in the remaining gaps in the immunity wall, and we’d shortly be able to declare the whole thing over.

As you can see, that’s not really what happened. We’ve certainly been nowhere near the level of the April 2020 and January 2021 death peaks, but COVID hasn’t exactly gone away either. Of course, some of this has been to do with the fact that restrictions have been removed, life is more or less back to normal for most people, and we are generally mixing again and having fun.

But certainly if your mental model was based around a “one exposure and you’re done” way of thinking, it’s been a bit of a disappointment - waning of immunity and the rise of an apparently endless succession of variants have left us bouncing around somewhere in the 50-90 deaths/day range for most of the last two years. The vaccines continue to mitigate the worst outcomes but, as plenty of people will remind you, #COVIDIsNotOver.

In the same way, people have been confidently predicting the imminent collapse of Twitter more or less since Elon Musk took it over. Of course, this could still happen, maybe just further down the line than people first claimed. I’m not convinced that’s the way it will go, but I’m not exactly optimistic about the site’s future either.

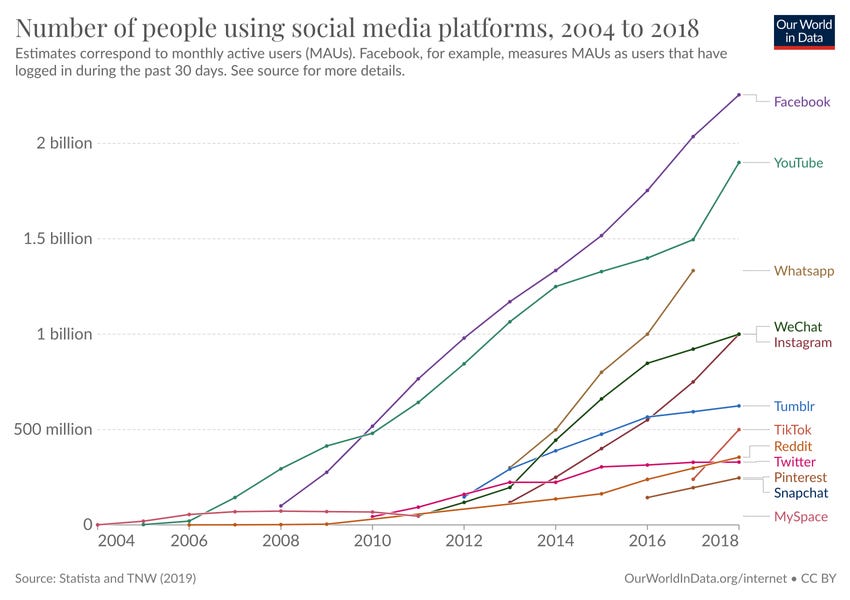

The key thing to remember is that Twitter has never been a huge player in terms of user numbers. This graph from Our World in Data shows how it’s been pretty static at a relatively low number of users (ok, the graph runs only up to 2018 but newer data here shows the same), while Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and all the rest of them have powered past it, headcount-wise.

However, Twitter has always had influence disproportionate to its user numbers, which is what made it an attractive takeover target in the first place. Of course, as a Twitter user I am biased to believe this, but things I’ve tweeted have ended up directly in outlets like Time, the New York Times, the Telegraph and many others, and I’m fairly sure that I wouldn’t have had that impact otherwise. Twitter was a place where journalists and politicians interacted, and which helped shape the news agenda. This was the site that the President of the United States himself used for his own (unique) form of international diplomacy!

The deliberate decision to deprioritise people like journalists by downgrading the value of their verified status doesn’t help keep it vital, but I think Twitter’s problems go far beyond what a blue tick does or doesn’t mean. For example, one of the great joys of the site has always been the real-time reaction to news stories. There’s been an army of smart people fighting to produce a meme or a gag, often going viral within a few moments of a story breaking.

For this reason, it felt like programmes like Have I Got News For You had a real problem. Why would you tune in to see the same clips, the same funny photos, even some of the same jokes delivered in a set timeslot three or four days after the Twitter version had been shared around? And yet … people did. Have I Got News For You will shortly be starting its 65th series, and will probably match the 4 million viewers per episode it had in the previous one. But at the same time, the show just doesn’t seem as important it once did - the run of BAFTA nominations has dried up, for example. But the show is still going.

However, just as Twitter made these programmes seem less significant, my feeling is that Twitter itself will just slowly decline in influence. Like COVID, it may well become something that gradually matters less to many people. Just as there wasn’t with the pandemic, I don’t expect there to be a single moment when we all incontrovertibly agree that it’s over. But it’s striking for example that, despite being unbanned in November, Trump hasn’t felt the need to come back.

My sense of the likely endgame for Twitter is that the network effects which caused it to be influential in the first place will gradually fade away - fewer interesting people will be there if there are fewer interesting people to hear from. The jokes and memes won’t spread as fast if fewer people are sharing them, and there are fewer funny people to spark off in the first place. Endless tinkering with the interface and display modes is already leading to a slow downgrade in the user experience.

Worst of all, what was once a funny place may well become a cringe place. If every time I log in, I am presented with a 10-year-old meme that reminds me that the place is being gradually taken over by crypto bros, I’m just not going to want to hang out there as much. Already I find myself there more for the DMs than for the content (I’m on a break from my main account this week, and I’m not really missing it).

But it’s worth remembering that even notorious flops like boo.com lived on as ideas and brands long after their original collapse, and for the same reason I think that even as a legacy brand, Twitter will exist in some form for a long time to come, even if in nothing like the form that made it shape the world's discussions in the past.

(Irony corner: do please prove me wrong about how Twitter isn’t as important is it used to be by sharing this piece there, and do please prove me right by subscribing to this Substack as well)

I guess you don't want any twitter memes

https://twitter.com/joshcarlosjosh/status/1642017647020900353?s=20