Last week, The Times reported a breakthrough in our thinking about ultra-processed food from a “top nutritionist”. Apparently

demonising all UPFs is a vast oversimplification that has caused stress to many consumers,

so we should be taking a more nuanced view and considering foodstuffs on their merits. While this may seem obvious, it was hard not to have a Jed Bartlet headdesk moment on reading it. The nutritionist in question works for ZOE, who have done as much as anyone in pushing exactly this kind of simplistic message. And while we might have a “more joy in heaven for a sinner who repents” feeling, lots of other people have been making the same points for years and being attacked as “a paid mouthpiece” of the industry by ZOE as a result.

But if the rhetoric around ultra-processed food is flattening out, and the discourse has moved on to Adolescence and killer 13-year-old incels, can we learn anything about these kinds of moral panic, and how to avoid getting sucked into them in future? I think there are at least five things that such stories need to get going, and I’d like to talk about how they arise and how to push back against them.

1. An important underlying problem

These stories don’t exist in a vacuum, and clearly they need something to get them going, ideally the kind of thing that nobody can be against. Who would be in favour of unhealthy kids, or misogynistic stabbings?

This has the effect of deadening the debate, because it sets up a motte-and-bailey fallacy. If you argued that keeping schools closed for months wasn’t proportionate or necessary to tackle COVID, you were in favour of killing granny. If you suggest that the NOVA classification of ultra-processed foods might be simplistic and unhelpful, you are denying that obesity might be an issue.

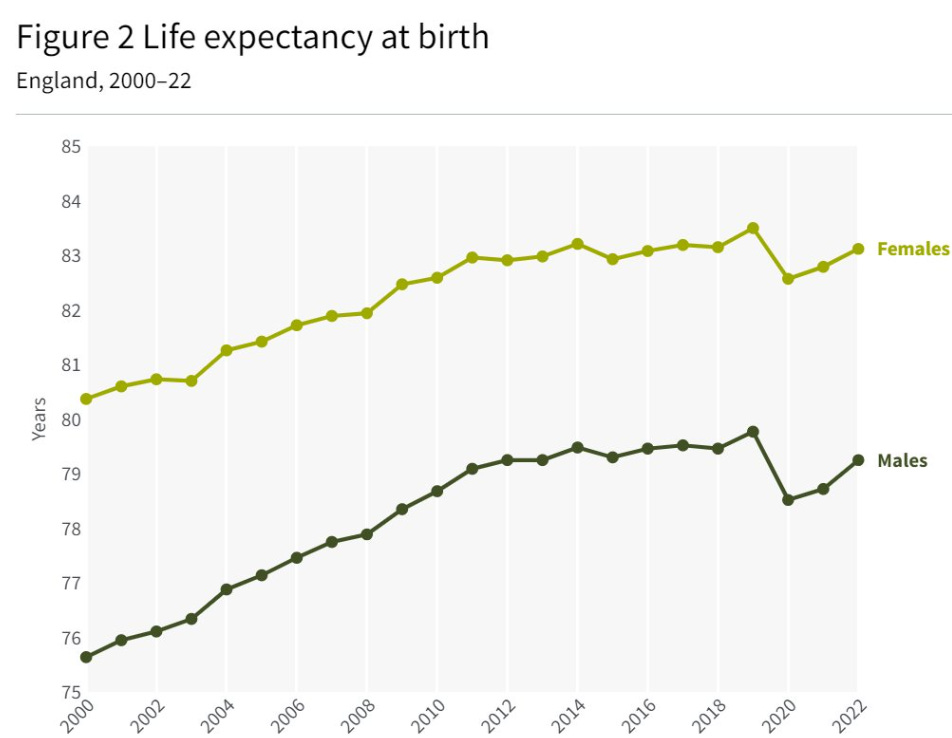

I think the best way to argue back is not to deny the problem exists, but rather to clarify its scale and trend. As long ago as 2005, Jamie Oliver notoriously claimed that unhealthy food meant “this is the first generation of kids expected to die before their parents”, and it is tempting to get sucked into rhetoric about falling life expectancies and rising obesity. However, up until the pandemic years at least, the data shows a clear increasing trend in life expectancy (albeit with a slowing rate of increase).

So maybe things could be better, but it’s not necessarily clear that it’s a five-alarm fire. In the same way, amid the discourse around Adolescence, it’s not unreasonable to ask what proportion of the horrifying toll of women’s deaths at the hands of men was due to scenarios of the kind depicted in that drama, compared to the 61% due to current or former partners for example.

2. A simple one-club solution

In order to build momentum, campaigns need to offer easy answers. It’s always tempting to think that there’s one simple change that can be transformative. We just need to tax UPFs, or ban teenagers from social media. There’s nothing more frustrating than to think that there’s an easy answer that’s being ignored, and these stories tap into that.

However, I think we should be mindful of Ben Goldacre’s slogan that “I Think You’ll Find It’s a Bit More Complicated Than That”. People and their interactions are far more subtle than a simple physical system, and it is rare that one problem has a single cause. As Mencken said, “for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong”.

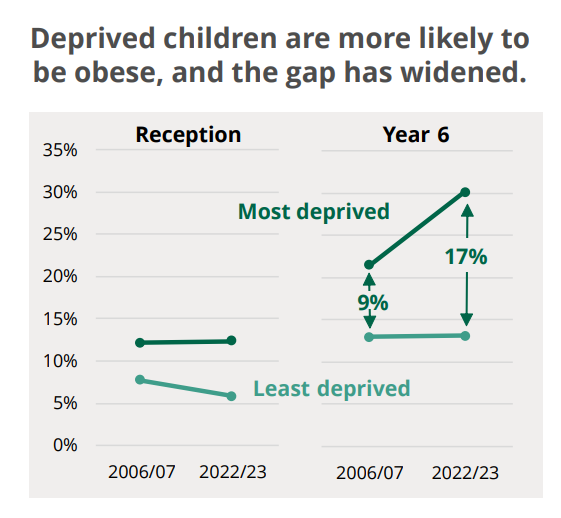

For example, we know that obesity in children is strongly linked to deprivation. Perhaps that simply reflects a situation where UPFs are cheaper, but it’s not hard to think of other mechanisms as well. Perhaps poorer children are more likely to attend schools without playing fields? Perhaps their families are less able to take them to sports clubs? Perhaps they have less access to garden space or safe neighbourhoods where they can roam without their parents worrying?

If that’s the case, then even a well-intentioned change might have less effect than we expect. If there are other more significant factors, perhaps we are wasting our energy and money by focusing on this particular one. And of course, things could be worse still - there might be second-order negative consequences to a well-intentioned decision. If closing schools for COVID might have caused a rise in mental health problems among girls, is it not at least plausible that removing access to their friends and support networks by shuttering Instagram and Tiktok might do the same?

I submitted a (short, non-technical) paper this week for a discussion at the Royal Statistical Society, arguing that the least bad answer might not have been “no lockdowns” or “long lockdowns” but rather some kind of short but focused response. In the same way, I think we should be careful to not get sucked into thinking that our problems have a single cause that we can magic away with a simple solution.

3. Everybody’s talkin’

On multiple occasions in the last 3 years I’ve been contacted by journalists wanting a steer on the latest omicron variant - was it likely to cause trouble? Generally, the answer has been no. I’ve given a growth rate estimate which implied it was unlikely the variant would cause a significant wave. And yet, the story still got written.

Understanding this helps us understand how the news gets reported. In these cases, the journalist wasn’t necessarily writing because they wanted to, but because other papers were reporting the variant and their news desk needed a story that did the same. With Google News, it’s possible to track the zombie statistic of “LP variants at 60%” (actually nine cases out of fifteen) that I wrote about last week as it bounces around the world.

In his 1972 work which popularised this idea of a “moral panic”, Stanley Cohen identified the key role played by the media. It’s not hard to see this effect in the debate around Adolescence, and the way that debate has gone viral. Once enough columnists were writing about the programme, it was hard for the Prime Minister not to get sucked into the arguments about it, and Starmer’s intervention itself became enough to reignite the coverage. By now, we’re probably past the backlash and somewhere into the backlash to the backlash, as the discourse perpetuates itself and looks for more hot takes on “the show that everyone’s talking about”.

Of course, Netflix aren’t going to complain about this. They are in the entertainment business after all, and phone-in hosts aren’t shy of controversy either. But as members of the public, we can at least choose whether to get sucked up into this feverish level of discourse. It’s reasonable to ask: if there’s a problem then why are we talking about it now? Are things worse than they were before it became the hot topic, or are we just more aware of it? It’s easy to get sucked into the Baader-Meinhof effect, and think that an issue has become more important because it is suddenly more visible.

But as the UK’s debate over its Assisted Dying bill has shown, it’s far from guaranteed that good laws emerge out of intensive media campaigns. It’s surely better to reflect and get it right (particularly in the light of point 2. above) than to make hasty moves that risk making things worse.

4. Follow the money

It’s worth being aware that issues do not spontaneously jump into the public and media consciousness. Just as each Oscars season sees a huge campaign of lobbying and PR, many stories are given a helping hand by one group or another. In the case of Adolescence, the charity Tender gave it a substantial push via press screenings and well-positioned op eds.

Of course, this is not sinister in itself. Charities have particular aims and issues to highlight, and in my view the fact that they may receive Government funding is neither here nor there. But at the very least, for news consumers navigating the media landscape it’s worth at least being aware of these issues.

There’s a bewildering variety of well-funded astroturf groups out there, often with appealing-sounding names. Who could object to taking advice on health matters from “America’s Frontline Doctors” or the “Independent Medical Alliance” after all? Except, if you click on the links, it may become clear that these may not exactly be disinterested and neutral bodies with no axe to grind.

This isn’t a partisan point - I’m no fan of the fact that Independent SAGE’s partners The Citizens have received $450k in grants from the Open Society Foundations (in 2021 and 2023) and $1.425m from Luminate either. But at the very least as media consumers it’s sometimes worth asking who the bodies being quoted are, and remembering that it may not be a simple David and Goliath story where we should reflexively back the underdog.

5. Folk devils

A key part of Cohen’s thesis about moral panics was the idea of a folk devil, an easy target on which all the wrongs can be pinned. Of course, this goes beyond my point 1. about identifying a problem. It’s much more convincing if someone is to blame, that a wrecker is making things worse deliberately.

This may even be true. Andrew Tate is not exactly an appealing figure, with credible legal cases against him in a variety of countries, and a clear track record of misogyny. But equally, polling suggests that even among boys, twice as many youngsters have a negative view of him than a positive one.

That’s not to say that he can’t be influential among the minority who do support him. But it might suggest there’s a danger of giving him more prominence than he deserves, and that compulsory screenings of Adolescence may inadvertently raise his profile.

In terms of ultra-processed foods, again there is a clear folk devil in the form of capitalism. The theory goes that people left to themselves would eat healthily, and it is only the greed of corporations being all corporation-y which leads them astray (see for example this paper full of graphs in the journal Globalization and Health). Again, perhaps this is true, but personally I take the rosier view that people know what they like, and are entitled to seek it out.

Further, in an era when some on the left have convinced themselves that Luigi Mangione is some kind of hero and campaigners like Chris Packham are dialling up the rhetoric against named individuals, its not hard to imagining this scapegoating of capitalism evolving into something uglier. As Orwell famously wrote in Beyond the Whale there can be disturbing linguistic games played by

the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled. So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot.

At the very least, I think it’s worth being aware of this danger, and not focusing too hard on convenient hate figures to the exclusion of all else.

So, what’s the answer?

I don’t really have one, and it would probably be hypocritical of me to try. I can’t help feeling that we are all imperfect people doing our best, and it wouldn’t harm any of us to take a few more steps each day, spend a bit less time on our phones, and try to eat a few healthier things. But I think we can do that without going full Bryan Johnson or obsessing too much about the finer details of the NOVA classification. But of course, I’m as likely to be wrong as anyone else.

On the two-thirds/one-thirds view of Tate, perhaps we should be very worried. Total guess - but my guess is that it’s quite likely that a large proportion of the vulnerable or easily influenced kids are in the one-third and that there’s a bad-actor multiplier effect. In any case I think, without panicking, that it’s reasonable to try to slow down the diffusion of Tate-style content.

Your article is as usual balanced and nuanced. I was especially interested in the Zoe pronouncement. I know so many people who are obsessed with Zoe and have parted with huge sums of money. No doubt Prof Spector is a fine scientist but ‘fame’ can be addictive and when someone starts having unquestioning followers it becomes a cult and that is troublesome. Anyway enough. Have a lovely weekend and once again thanks for your lovely accessible articles.