This newsletter looks at the world and current news stories through mathematical eyes. While maths can’t tell you much about the coronation of King Charles III itself, it’s a good time to see how past Kings and Queens have interacted with the subject, so here’s my topical countdown of mathematical Royals. This ranges from a coronation date being decided by a mathematician, to a different King Charles inventing a new way to count, and a monarch who wrote their own geometry textbook - but I’d love to know who I’ve missed.

6. Charles II

The best place to start may be with the previous King Charles, who illustrates the role that many Royals have played in patronage and support for mathematics.

Charles’s interest in maths perhaps dated back to being tutored in the subject by Thomas (“Leviathan”) Hobbes while in exile. One of his biggest contributions came in his support for the fledging Royal Society, to which he issued a Royal Charter on 12th January 1662. The first president of the Royal Society was a mathematician, and it has been convincingly argued that this society helped mathematicians such as Isaac Newton to flourish and carry out their most important work.

Of course, Charles II wasn’t unique in creating an environment where mathematical scholarship was valued by enlightened rulers. Similarly important patronage was provided by Henry VIII, King Frederick the Great of Prussia and the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mun and others in Baghdad, for example. But in the days before research councils and grant funding, it is clear that royal support could give mathematicians an opportunity to thrive.

And even in more recent years, mathematicians have been recognised by the Royal Family in a number of ways. In particular five of them have won the highest British honour, and joined the Order of Merit since it was established in 1902 - and I’ll be impressed if you can name all five1.

5. Ptolemy I Soter of Egypt

Our next Royal is best known mathematically for the contribution that they didn’t make. Ptolemy I Soter began his career as one of Alexander the Great’s bodyguards, before rising to become his successor, and ruling as Pharaoh of Egypt from 304BC to 282 BC. During Ptolemy’s reign and with his support, the Greek geometer Euclid helped establish the city of Alexandria as a centre of mathematics and learning.

Euclid’s longest lasting contribution was in writing the Elements. This book formed mathematics into a logical structure, starting from a few hopefully uncontroversial axioms (self-evident principles) and building up a collection of theorems (significant results) via a chain of logical deductions. This codified the scientific method as it applies to mathematics, and still shapes the structure of all research today.

Euclid is particularly associated with geometry, although ironically one of his geometric axioms did turn out to be controversial, and systems of so-called non-Euclidean geometry are required to capture the ideas of curved spaces underlying Einstein’s work on general relativity. For example, if you draw a triangle on a football then the angles will add up to more than 180 degrees, violating Euclid’s assumptions.

In any case, Ptolemy I Soter not only acted as Euclid’s patron but also tried to learn mathematics from him, not always successfully. Famously, like many people Ptolemy found the rigorous study of geometry based on the Elements to be challenging, and asked Euclid for a simpler method. Euclid’s reply (as reported by Proclus) that “there is no royal road to geometry”, has passed into legend, and serves to remind us all that sometimes maths is just hard and that even the mightiest people can struggle with it.

4. Elizabeth I

Another Royal mathematical connection shows the way that the lines between science and pseudo-science haven’t always been drawn in the same places as they are now. Another illustration is the way that, following his fundamental work on gravity, optics and calculus, Isaac Newton devoted many of his later years to alchemy and the search for the Philosopher’s Stone.

But another great scientist of the time, John Dee, very clearly illustrates the blurred lines that could lie between the natural and the supernatural. Dee was the Court Astronomer to Queen Elizabeth I, developed the links between Euclid’s geometry and terrestrial navigation and was offered a mathematical position at Oxford University.

Yet Dee also spent much of his life dealing with magic and the occult. A mysterious figure around whom many myths have grown up, he appears in Umberto Eco’s book Foucault’s Pendulum as an focus of conspiracy theories developed by cranks, and is quite likely to have been the model for Prospero in Shakespeare’s Tempest.

While King Charles III presumably considered a variety of factors when choosing 6th May 2023 as the best date for his coronation, it is probably unlikely these would have included his horoscope. However, Elizabeth I’s coronation date of 15th January 1559 was chosen by Dee on the basis of astrological readings, showing just how the role of mathematicians has changed over time. Yet, Dee’s words in his preface to a volume of Euclid could have equally well worked for my own book:

All thinges do appeare to be Formed by the reason of Numbers.

3. Victoria

Britain’s second-longest reigning monarch Queen Victoria was not known as a mathematician, however she is the basis of a famous mathematical urban legend.

It is well known that Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, was a pseudonym for the Oxford mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. It seems that Dodgson may have suffered the fate of many people who try to balance popular and scientific writing, and have to try to separate these two aspects of their work:

A well-known story tells how Queen Victoria, charmed by “Alice in Wonderland," expressed a desire to receive the author's next work, and was presented, in due course, with a loyally inscribed copy of "An Elementary Treatise on Determinants."

Sadly, according to Snopes, this story is too good to be true. Indeed, Dodgson himself said “it is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred”.

However, Alice does have another royal connection with maths, through an analogy with one episode in the book. In mathematical models of evolutionary biology, the Red Queen hypothesis suggests that evolution is a continuing race, and that species must constantly develop if they are not to be overtaken by others. (This led in turn to one of the all-time greatest acknowledgment notes in a scientific paper). Even now, we see new COVID strains continually developing, pulling ahead of the pack, and gradually losing their advantage as new competitors emerge behind them ready to overtake.

2. Charles XII of Sweden

Having described a number of monarchs who learned or supported mathematics, at the top of the list come two Kings who actually made contributions to the subject themselves.

King Charles XII of Sweden led his armies against an alliance including Russia, Denmark, Norway and Saxony in the Great Northern War. His record included both military triumphs at Narva, Fraustadt and Holowczyn and defeats at Poltava and Fredriksten. Achieving all this, as well as political reforms and a period of exile in Turkey, before an extremely early death at the age of 36 doesn’t seem to leave much time for maths!

However, Charles was interested in anything that could help him make military progress. This included advocating for a system of octal numbers (base 8, as opposed to the standard decimal, or base 10). Here, you would count 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,10,11,12, … with the “tens” digit counting multiples of 8. Indeed Charles even argued for base 64 to become the standard. The numbers 8 and 64 were apparently chosen because they are perfect cubes, and so allowed quick counting of stacked boxes of gunpowder and other materials.

Legendary computer scientist Donald Knuth wrote in Volume 2 of his masterwork The Art of Computer Programming that:

Charles XII of Sweden, whose talent for mathematics perhaps exceeded that of all other kings in the history of the world, hit on the idea of radix8 arithmetic about 1717. This was probably his own invention …

The final entry on this list might suggest that Knuth’s claim about Charles’s pre-eminence is not certain, but equally it seems clear that King Charles XII should be remembered for making novel mathematical contributions as well as for his military efforts.

1. al-Mu'taman of Zaragoza

So, who is my top Royal mathematician? He’s not exactly a household name, but definitely deserves to be. I give you Yusuf al-Mu'taman ibn Hud, or al-Mu'taman for short. He reigned in the Muslim taifa of Zaragoza in Moorish Spain from 1081 to 1085 (so at the end of William the Conqueror’s reign in England). As King, he had to navigate a series of shifting political rivalries between similar states, but also

created around him a court of intellectuals, living in the beautiful palace of Aljafería, nicknamed as "the palace of joy".

But as well as being a patron of the sciences, al-Mu'taman was also a mathematician of some distinction in his own right. He wrote a textbook called the Kitab al-Istikmal, which summarised a large number of existing results in geometry and other fields, going beyond Euclid’s Elements.

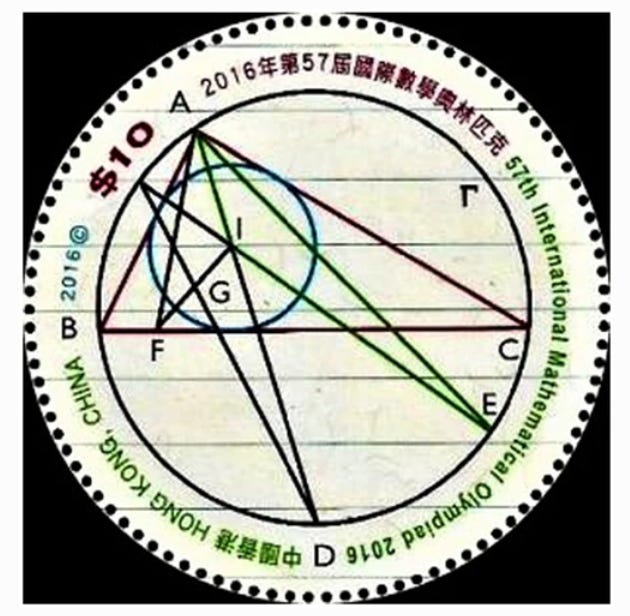

In particular, the Kitab al-Istikmal was the first text known to describe what is now known as Ceva’s Theorem, which was named after its “discoverer” who published it nearly 600 years later and commemorated on a stamp issued for the 2016 International Mathematical Olympiad as described here. This result describes a fundamental property linking the ratios of lengths of lines that arise when drawing three lines through any point inside any triangle.

While we may never know for sure whether al-Mu'taman discovered this result himself or simply reported results known locally at the time, there is a convincing argument based on an analysis of recovered parts of the text that

Al-Mu'taman was one of the leading pure mathematicians of the Islamic Spanish tradition.

Certainly by any standards he has an extremely strong claim to be the most impressive mathematical monarch of all time. Whether or not you celebrate King Charles’s coronation, it’s worth remembering the contributions that King al-Mu'taman made, almost a full millennium ago.

Which Royal mathematical connections did I miss? Let me know in the comments. And please do check out my list of recommendations to find other Substack authors. If you haven’t read my book Numbercrunch yet then you can order it here - and if you have read it then please leave a review either there or at Goodreads. Thank you!

Mathematicians who joined the Order of Merit are Whitehead, Russell, Penney, Penrose and Atiyah. I love the idea that one person who played a huge role in getting Britain atomic weapons, and one person who played a huge role in trying to stop them got exactly the same award, even if they hardly coincided in holding it.

Nice list. I'll throw in my favourite: Ulugh Beg of Samarkand, Timurid Sultan, and grandson of Tamerlane. Built an enormous observatory housing a 40 metre sextant which made astronomical observations of such accuracy that were only matched in Europe in the 19th Century. Founded schools of mathematics that attracted the leading mathematicians of Central Asia (which at the time, meant the world), and led their discussions of mathematical problems personally, showing world-class ability in trigonometry and spherical geometry.

Sadly, far more interested in calculating specific values of sin(x) to 12 significant figures than noticing that his own son was about to stab him in the back (literally) and take his throne.