Fool me Tice, shame on you

Here comes the new boss, same as the old boss

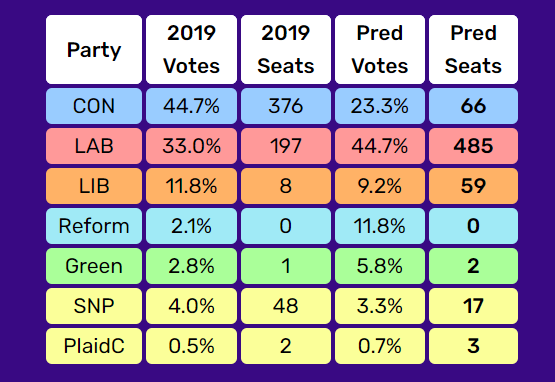

As I mentioned last week, the UK is in a General Election campaign, and a key factor remains the proportion of Reform votes. Last night’s MRP poll showed that they have the potential to act as a considerable spoiler for the Conservatives while doing little directly for themselves: 12% of the population voting for Reform brings them no seats, but also pushes the Conservatives to 23% and only 66 seats. Obviously if those 35% all voted Conservative then the margin of Tory defeat would be much smaller.

In that sense, since Reform are such important players in the eventual outcome, I thought it was worth scrutinising their platform a little bit. Instead of a manifesto, they have what they call a Contract, but it amounts to the same thing. There are lots of policies to do with slashing bureaucracy and DEI and so on, to Get Britain Working Again. But in the NHS section there’s something quite worrying to me:

Excess Deaths and Vaccine Harms Public Inquiry.

Excess deaths are nearly as high as they were during the Covid pandemic. Young people are overrepresented.

Now of course, as with any medical intervention, there were side effects to the COVID vaccines. Some people even died as a result of them, and that’s a tragedy. But of course the counterfactual is that for many people COVID would have been very much worse without vaccination, and I have no doubt at all that on a population level the widespread deployment in 2021 was a big win. (But I have no problem with the JCVI being cautious in considering the risk-benefit analysis of further boosters among the non-vulnerable population right now).

Indeed, I believe that Reform’s claim about excess deaths, with the accompanying innuendo that vaccines are currently causing nearly as many deaths as at the peak of the pandemic, is a straightforward lie. I am extremely disturbed to see this kind of antivax rhetoric crossing the Atlantic and popping up in the platform of a major British political party, so I wanted to delve into where it has come from.

Show me the numbers

As I described in Numbercrunch, calculating excess deaths essentially involves the difference between measured and expected deaths. The problem with this is that to know what is expected, you need to do some kind of statistical modelling, which is where the waters start to get murky.

I think a representative example of the excess death claim is the article by Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson published in the Daily Telegraph on 21st February 2024. Within it, there’s some sleight of hand, I think:

As always, we can trust the evidence. And what we can see in the data is that, since the pandemic, deaths have remained high in all three of the ensuing years – above 650,000 annually across the UK. Compare this with 2011, when just over 550,000 deaths occurred. Changes to the size, age or gender of the population seem unlikely to explain an increase in 100,000 deaths over this period.

Now, the numerical values here are correct. But I reject entirely the claim that the changing population seems unlikely to explain the difference. The clue is in the use of 2011 as a reference date, because that was the year of minimum deaths:

Indeed, we can see that there was a significant rise in deaths in the decade after that: every year from 2015 to 2019 saw around 600,000 or more. So it seems extremely curious to say that 650,000 deaths represents a big jump from 550,000 in 2011, rather than to present it as a smaller jump from 610,000 or so pre-pandemic. And of course, we expect a jump during the pandemic itself, because it was a pandemic, and we know that tens of thousands of people were dying each year with COVID on their death certificate!

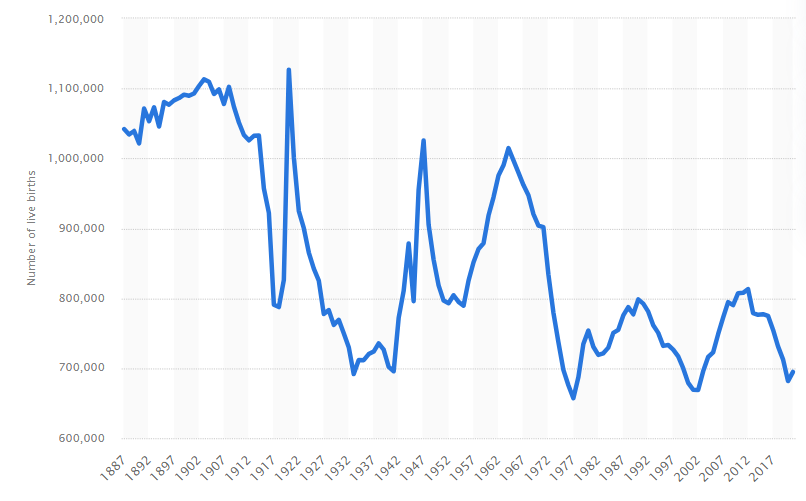

But why should there be a rise from 2011 to 2019? An obvious answer might be to blame the Conservatives and austerity, but actually to some extent it was baked in decades ago. That is, we are all aware of the postwar baby boom, but it’s important to realise how in terms of scale and size it matches the timings of the increase in deaths:

That is, in the decade or so following the war, we saw around 200,000 more births each year than previously. All these people will have different life spans, and so the tight peak in births will be spread out in terms of deaths. But you don’t need to be a Professor in Evidence-Based Medicine to work out that the cohort of people born in 1945 would reach age 70 in the middle of that decade of interest, so it’s not surprising to see deaths starting to increase around then.

Of course, this is extremely crude, modelling-wise. People like Stuart McDonald on Twitter do a much better job of it, stratifying properly to work out what we would expect to see given our ageing population. And you can see from Stuart’s graph that so far 2024 is working out very well indeed:

At the moment, the solid dark line is not just below the 2014-2023 average (we’d hope for that, given improvements in medical care), but so far we are tracking 2019, the single best of all these years. In that sense it seems very hard to understand Reform’s claim (and indeed it’s hard to understand claims that COVID itself is directly or indirectly causing large numbers of deaths now).

That all seems like good news, but there was one more claim in the Reform document. That is, it could be that significant increases in deaths among young people are being masked by an overall decline in the old.

Here you have to be slightly careful, because deaths among the young are so rare. It’s often the case that such deaths are reported late, because of the need for coroners’ inquests, and so a delay in inquests during the pandemic can confuse the picture for example.

However, a proper analysis exists in the Mortality section of the Scottish COVID dashboard for example, with weeks colour-coded for the level of deaths, and split out by age:

Overall, you can see that it’s an extremely positive picture. Apart from a few weeks at the end of 2022 and start of 2023, when deaths got higher than expected in the old, the picture is overwhelmingly green (“baseline”) with only one or two weeks showing up as yellow (“low”) in certain groups.

Based on all this, then, the picture regarding current excess deaths in the UK seems extremely positive. It seems very hard indeed to justify Reform’s claim, and people planning to vote for them need to have a serious think about whether this is the kind of argument that they would like to see taking hold in British politics.

Regardless of the bad science, it just baffles me that Reform would think people still care about this in 2024. The pandemic was an awful time we all want to forget about rather than tediously relitigate.

I too am concerned by the anti-vax rhetoric and also misinformation that is being peddled by Tice and also by Farage in their appearances whilst canvassing in the election. With such people I wonder if they genuinely lack an understanding of the facts and interpretations, or whether they think it is expeditious to their political aspirations to jump on a populist viewpoint, no matter how much of a misconception it is.