Power games

We got a love between us and it's like electricity

All we need to do is “Follow the Science”, and we can get the Bad Things down to zero and lead a better life. Sounds great, doesn’t it? But having heard these kinds of promises in 2020, should we trust them again in 2024?

Last week, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called a general election in the United Kingdom. It’s well accepted that his party are going to lose, and lose badly. As someone who crunches numbers and tries to test out alternative viewpoints to the orthodox ones, you might perhaps expect me to model a different outcome.

Well, I can’t. If you are after well-informed academic commentary on the UK election on Substack, you should be following people like Rob Ford and Ben Ansell. All I can give you is memories of 1997: it feels clear to me that there has been a vibe shift on a similar scale, and that once again tactical voting between Labour and LibDem supporters has the potential to deliver exactly the right amount of local swing to reduce Conservative seats very low indeed. In fact, I suspect that Sunak would take the 165 seats the Tories gained in 1997 if he was offered them now.

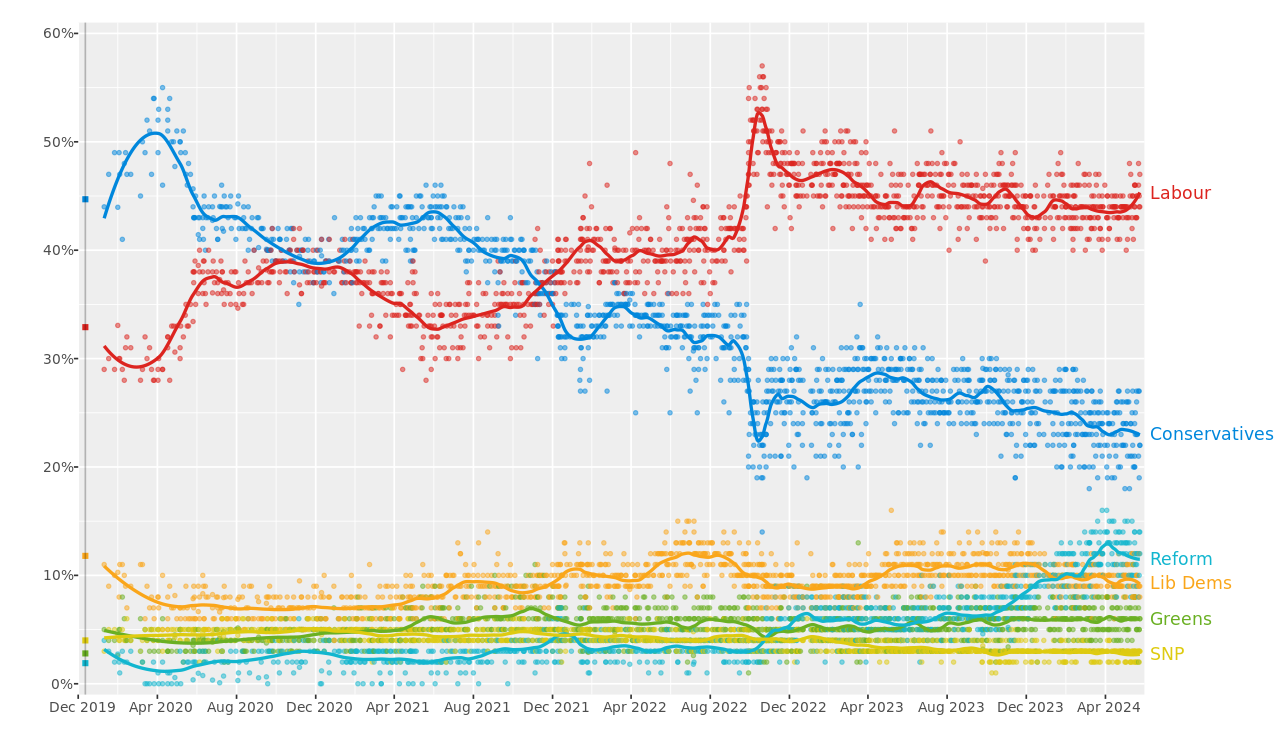

So, why call the election? I think the answer is very simple. The Wikipedia graph of polling shows that, after a brief revival following the Truss interregnum, the Conservative vote share has been drifting consistently down since April 2023. Waiting longer presumably projects this trend out into the future:

And since the main movement has come rightwards from Conservative to Reform, not towards Labour, Sunak is essentially calling Reform voters’ bluff. That bloc of voters probably has the ability to determine whether Starmer wins with a 200 seat majority or with something closer to say 50, and calling the election forces them to make that choice now, rather than at a time of potential Reform-Conservative crossover. (Of course policy announcements like National Service need to be viewed through this lens, not in terms of how they play on left-leaning Twitter).

But it seems extremely hard indeed to come up with a narrative whereby Prime Minister Keir Starmer is not standing on the steps of Downing Street on July 5th. Since that’s less than six weeks away, and since he (and many of his likely Cabinet) has never held ministerial office, it’s reasonable to ask how he might play things.

For example, the one month deadline imposed on Israel by the International Court of Justice will have recently passed, and it seems quite likely that the Netanyahu government will have ignored it. Right at the top of Starmer’s intray will be the question of how to respond: whether to stop arms sales, to recognise a Palestinian state, to do other things that his party might demand. Within four months, it’s quite possible he will have to deal with the implications of a second Trump term. It would be nice to think that at some stage in the campaign, these matters might be discussed so that the electorate can make an informed decision.

But there are less immediate but perhaps even more important issues in the new Prime Minister’s remit. For me, the key one is our ongoing energy supply, and how we balance the need to act on climate change with the desire for a strong economy. As I described previously I don’t believe that these are simply matters of science, but rather questions of economics and engineering.

In that sense it was pretty frustrating to read Ed Miliband, the man who is likely to be delivering these policies, saying that:

Labour plans to “follow the science” when it comes to climate policies, should it come into power. If Labour wins, he said the UK would “be the first major country in the world to commit to having all of our power coming from zero-carbon energy services by 2030, which is a massive commitment and requires massive change”.

For me, this “follow the science” mantra was one of the most depressing ones of the COVID years. What was worse about Miliband’s quote is that he delivered it at a joint event with Sir David King, the man who formed Independent SAGE. It was King who infamously argued on 14th July 2020 that schools should not reopen until we reached Zero COVID, for example.

Indeed, for much of the pandemic Labour followed the Independent SAGE line. In May 2020, Deputy Leader Angela Rayner boosted the ISAGE report arguing for continued school closures (confusing them with the real SAGE in the process). Starmer himself warned that the July 2021 reopening would cause 100,000 cases per day, tweeting about the so-called “Johnson variant” in language straight out of the Independent SAGE playbook. In October 2021, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves called for a return to working from home and masking.

While it’s perfectly reasonable to argue that the Government was too slow to respond to the spring and autumn COVID waves of 2020, it’s also reasonable to ask whether Labour were too slow to respond to the changed reality that the vaccines brought. Further, it’s reasonable to question whether in a UK which already saw hundreds of clusters formed by independent COVID introduction events in spring 2020, whether Zero COVID was ever a realistic option, despite what some groups of Labour MPs advocated.

So, in that sense, it seems reasonable to ask whether Miliband’s idea that we can just “Follow the Science” and reach zero carbon electricity by 2030 is feasible, or whether it represents a failure to learn from past mistakes regarding science communication. It’s important to note that this isn’t an argument about decarbonising the grid altogether: while we still wait for the Conservative manifesto, current Government policy is that this will be achieved by 2035.

It’s not an argument about whether, it’s an argument about how soon it can be done. And it feels to me like a good test of governance: how deeply have Labour engaged with the reality, who have they been talking to who have convinced them that 2030 is possible? Again, it would be nice if journalists could get answers to some of these questions.

I asked around on Twitter, and while I got some interesting replies from people in the energy sector, the consensus was that 2035 was already very ambitious, but 2030 would be a serious stretch. The closest I was given was this report from Public First. But even this report isn’t exactly gung ho about the prospect. It says that

we argue that the 2030 target is not impossible – merely very difficult – and that it presents an ambitious goal for industry and the public to rally behind.

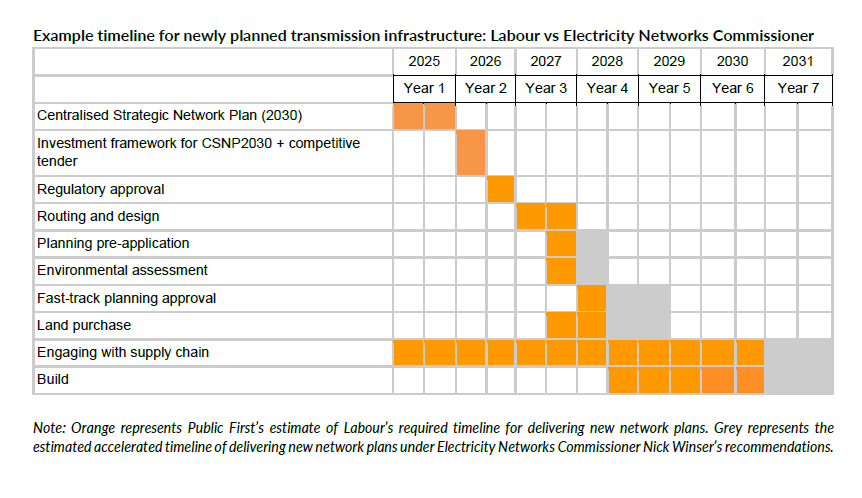

In some sense, as with Matt Hancock’s infamous 100,000 tests per day target, it’s very arguable that aspiring to an overambitious goal may have benefits even if we don’t achieve it. And the report does set out a roadmap as to how 2030 might be possible, even if (given the speed at which things happen in the UK) we might wonder how likely it is that we can achieve planning approval in just six months to expand the grid by the requisite massive amount, for example.1

But as with Zero COVID, even within the Public First report I detect a certain amount of goalpost shifting that wasn’t present with Miliband’s quote about “all of our power coming from zero-carbon energy services”. On interrogation, it eventually turned out that Zero COVID didn’t mean literally zero. In the same way, the Public First report actually says that 1.2% of our electricity will come from gas, with half of the resulting carbon being recaptured.

It may sound pedantic, but there’s a difference between 100% and 99.3%, and I’d much rather have politicians be upfront with me about this, than offering easy soundbites. Even 1.2% seems ambitious to me, given that (even with interconnects and future increases in storage capacity) we need to battle long periods in the winter with little wind or solar power. But I’m currently in Jed Bartlet mode:

“Numbers, Mrs. Landingham, . . . if you want to convince me of something, show me numbers.”

Maybe you can’t expect a more detailed analysis from a politician speaking at a literary festival, but there are fewer than six weeks until I need to know how to answer these questions, in order to judge the seriousness of the Labour offering when I head to the polling station.

The report talks about even to reach a 2035 target that we must “install over five times more transmission infrastructure over the next seven years than has been delivered in the last three decades”

One point I'd make is that In the medium term the desire for a strong economy and for a low carbon economy should be the same thing rather than being opposed.

However, I work in the energy transition and agree that the 2030 figure is "challenging"! In reality it's probably not possible though the scale and increasing speed of the transition around the work is often surprising, for example, the growth of solar PV has consistently outstripped predictions.

The UK electricity grid and associated generation assets are a different matter though, the scale of the infrastructure and the transition creates logistical and supply chain scaling realities that we will struggle to overcome.

I do wonder why this target has been selected as for the majority of the public I fail to see the difference between a 2030 and a 2035 target. When I see these kind of targets I am reminded of Extinction Rebellion and their 'net zero by 2025' demand which was scientifically illiterate and disingenuous and ultimately self defeating, good at rallying people in 2019, making them look stupid in 2024.

As someone who works in climate change we need to be both more ambitious and more realistic which is why I like the work of Hannah Ritchie who manages to walk this balance.

I agree with you that I can't see wind and solar providing the full solution to net zero, because I can't see that there is a feasible energy storage capacity on the horizon that would be capable of bridging periods of low wind and low sunlight. It's a pity we're starting from where we are, because nuclear power is a viable technology and does have the technical capability to supply our total base demands, with France being a good example of what has been technically possible. The trouble is that building new large reactors takes a long time because of planning issues and we don't know how quickly small modular reactors could be rolled out. Opposition to nuclear at a political and social level has always been a drag on its progress, because fears over the dangers haven't been rationally based on hard numbers. The world has seen far more deaths by orders of magnitude due to fossil fuels, and hydroelectric dam failures, than have ever resulted from nuclear accidents. The problem is that the development of nuclear power has been as a parallel to development of nuclear weapons and we have reactors based on Uranium and Plutonium. However we've also been using other radioactive sources for many decades in medicine and these materials are widely distributed in hospitals and Universities and in industry with social acceptance of the risks. Power reactors using isotopes that are not associated with weaponry could have been developed, a missed opportunity.

However we are, where we are, and we need technologies to provide the base load requirements when the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing.