Here’s a short piece about Science Communication. On June 7th 2024, “physician-scientist, author, editor” Eric Topol sent the following tweet:

While he promised a thread, the only follow up was this one:

I believe that this is a bad example of how to communicate complex scientific findings, and may have counterproductive effects on public health. Coming from someone who has 695k Twitter followers, and 105k subscribers on this platform, I think it’s very much a case of “could do better”.

On some level, the question is simple: as a member of the public, would reading Topol’s message make you more or less likely to get a booster shot this autumn? I believe that the answer is “less likely”. We all know from our experience with flu vaccines that sometimes the year’s choice of vaccine doesn’t match the circulating strain and the flu season is worse as a result.

Reading Topol’s tweet, it seems natural to conclude that the same is happening here. You can see many of the quote tweets shrugging their shoulders, and deciding the authorities are incompetent. At a time when COVID is gradually dropping from the news, it’s a marginal decision for many people whether to get the next booster, so hearing even second-hand that “a doctor said that this year’s COVID booster isn’t a good one” is likely to be a tipping point for some. (Of course, if Topol wishes to argue privately with the CDC or others for boosters based on KP.3 that’s a different matter).

However, personally, I’d stick with the Gretzky principle:

You miss 100% of the shots you don't take

The question is really “should we let the perfect be the enemy of the good?”. Is it likely that having even a mismatched booster is better than no booster? Now, I’m not an immunologist, a virologist or an epidemiologist (though nor is Dr Topol), but I am aware of people who are. For example Marc Veldhoen writes here that “any contact with SC2 spike protein will boost your anti-COVID-19 response”:

(Unfortunately, this tweet has a fraction of the visibility of Topol’s).

In general, it seems to me that talking in terms of matched or mismatched boosters risks falling into a trap of binary thinking. It feels much more plausible to me that any booster based on any strain will have some effectiveness, the only question is “how much?”. If this wasn’t the case, we’d all be infected with every single mutation that came round, which we know isn’t true. Further, it seems to me that the more similar the original and mutated strain, the better the protection is likely to be.

Of course, this isn’t our first rodeo. Last winter, we faced the BA.2.86 strain and later its JN.1 offshoot, with protection largely based on vaccines developed for XBB (and even earlier mutations in some cases). And how did that work out? Well, despite Topol’s pessimism at the time, even he had to admit that there had been a good degree of protection:

(In that sense it was ironic to be lamenting the lack of take up!). In the UK, Table 2 of the UKHSA vaccine surveillance report estimates that protection against hospitalization in the over 65s was 36.6% (albeit with wide confidence intervals).

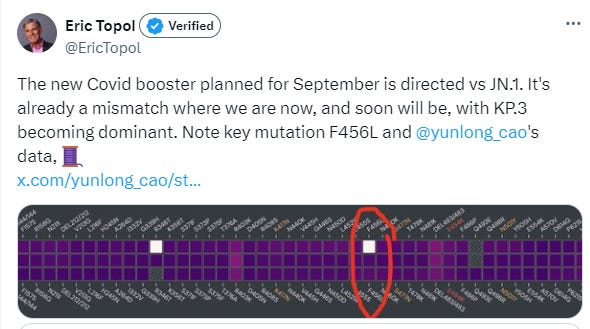

And that feels like a much bigger mismatch than the current one. There was a big jump mutation-wise from XBB to BA.2.86. Whereas KP.3 is very much in the same family as JN.1 (technically speaking, I believe KP.3 is BA.2.86.1.1.11.1.3, JN.1 was BA.2.86.1.1 - there’s a pretty strong family resemblance!).

So, for me, it doesn’t seem like a good idea when talking to a general audience to highlight a couple of “key mutations” taken out of context, without trying to calibrate how significant they are likely to be, and how much of an effect they might have.

We’ve seen already from UK hospital data that the move from JN.1 to the so-called “Flirt” strains (such as KP.3) has caused some increase in admissions. But the effect of this has been extremely limited, consistent with the small growth advantages estimated from sequencing data by Dave McNally, and it’s quite plausible that the resulting wavelet has already peaked.

Unfortunately, for all his sizeable audience, in my view Topol’s messaging has more than once left something to be desired. For example, I previously wrote about how the message that “you won’t see increases in hospitalization until a strain hits 50%” was a misleading one. This claim was uncritically promoted here

Recall that it takes a level of 50% or greater to see the real impact in terms of clinical outcomes such as hospitalizations.

for example. Further, just as replies were turned off on the tweet I mentioned above, it wasn’t possible for me (as a non-paying user) to reply to his Substack piece to correct it.

I think it’s important to remember that with Scicomm, as with many other things, with great power comes great responsibility, and that those people blessed with a particularly large audience have a responsibility to make sure that the information they are presenting is properly contextualized. I don’t believe that the original tweet did this.

Yes I agree, the message conveyed the wrong impression to such a large and diverse audience, the vast majority of whom would lack the scientific knowledge to appreciate any subtleties and nuances. The problem is that immunology is an incredibly complex subject and it takes years of study to even gain a knowledge of a fraction of that complexity. Fortunately for us the immune system generally works well without our understanding, evolution and natural selection are powerful forces.

The crucial thing is that our immune system has surveillance for multiple aspects of an infectious pathogen such as SARS-CoV-2. T-cells and B-cells also tend to see different aspects of viral protein structure. B-cells are more focussed on the 3-dimensional tertiary structure, whereas T-cells are more focussed on the peptide sequences, primary structure. You also have a polyclonal cellular (T and B-cell) response seeing multiple primary and tertiary “epitopes” of the virus protein. As the virus picks up mutations it tends to knock out the ability of some B-cell clones and some T-cell clones to see and respond to the virus. However the virus is also constrained in that any mutations it makes in its proteins might impact adversely on essential functions of those proteins. What this means is that even a partially matched vaccine will boost sufficient numbers of T-cell and B-cell clones that you will have a quicker response to a new infection compared to if you hadn’t been vaccinated at all. Obviously the better the match, the better the response, it’s a quantitative effect and not a qualitative binary yes or no effect.

As with a lot of posting, it seems he got more caught up in the status game than trying to give important context. It is at least more accurate than most of financial, economics and politics twitter posting.