I've come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

1. Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that's invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

Fiat Lux

For much of the world, something very much in Adams’ first category of technology is electric light. It can be hard to understand what a big deal it is, but for most of human history the world would have literally been a very dark place, at least in the latitudes I live in.

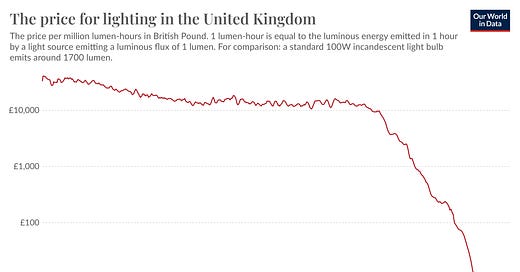

This is best illustrated by one of my favourite graphs, which looks like it needs to be on a log scale despite the fact it already is on a log scale. It shows the inflation-adjusted yearly cost of the illumination you’d get by running a single 100W light bulb for a couple of hours per day. What you can see is that up until 1800 or so, even this amount of light was a serious expense. But from then, the price dropped exponentially (straight line on a log scale!) over the next couple of centuries, as new technology and more efficient manufacturing took lighting from an unimaginable luxury to being almost too commonplace to even think about.

But that graph hides the fact that for most of those two centuries we were generally getting light in a ridiculous way. Home lighting was mostly through incandescent light bulbs. While this moved from Adams’ third category to his first, it’s hard to ignore what a crazy way it was to make light. The technology essentially consisted of putting a sufficiently large electric current through a narrow bit of wire to make it very hot. (Anyone who tried to prematurely remove a broken 100W bulb can testify to this!). Almost as a side effect, as the wire heated up it would glow brightly.

For all that they improved on candles and so on, incandescent bulbs were a crazily inefficient way of lighting a room. Only around 5% of the electrical energy used was turned into light, and in the not-particularly-well insulated houses of the 1980s and earlier, the remaining 95% tended to go straight through the roof. It was like cooking your dinner by wrapping it in foil, putting it on the engine block of an expensive sports car, and going for a drive. It worked, but there had to be a better way.

Generation next, generation next

What happened next was the development of the compact fluorescent bulb. These seemed far better: for a start they were about five times more efficient. And because their operation didn’t involve heating up to a crazy temperature a thin wire which had a tendency to break after a while, they were more reliable: Wikipedia reckons they have eight to fifteen times the lifetime of their predecessors.

For a while (something like 1997 to 2012, say) compact fluorescent bulbs were an enormous deal. This was a new technology arriving about when Governments first started to take climate change really seriously, and it seemed like a no-brainer. In the UK at least, you couldn’t move for these bulbs. Power companies realised that literally giving them away could count towards their carbon emission targets. I remember getting half a dozen unsolicited compact fluorescents in the post for free one day. Some of them are still in a cupboard here.

But as nu metal stars will tell you, nothing lasts forever, and the compact fluorescents have more or less gone the way of Limp Bizkit. Part of the problem was the bulbs themselves. The chemical processes that drove them took a while to get going, so they were slow to warm up, which was always annoying. And while they had environmental benefits in terms of carbon emissions, they weren’t so good in other respects. Because their design relied on small but significant amounts of mercury, they could actually be pretty hazardous: councils and governments had to worry about how to dispose of them safely and keep them out of landfill. As a result, in less than a decade these bulbs went from being part of the climate change solution to being banned in the EU.

But the other thing that changed was that a new and even better class of bulb came along. Now we have LED lamps, which are essentially better in every respect. They are even more efficient to run, they last longer, they don’t take time to warm up and they don’t contain mercury. But the thing that really tipped them over the edge into ubiquity was yet another set of exponential performance increases.

You might have heard of Moore’s Law (governing the exponential improvement of computers over time) - if not then I discussed it in Numbercrunch. But there’s a similar rule for LEDs, called Haitz’s law which suggests that

every decade, the cost per lumen (unit of useful light emitted) falls by a factor of 10, and the amount of light generated per LED package increases by a factor of 20.

You can see this here - again note the straight lines on log scales! - exponentially falling cost, and exponentially growing efficiency. It’s an irresistible combination.

May the good Lord shine a light on you

So, why am I telling you this? Well, for one thing there’s a strong current of miserabilism about the state of the world. You regularly see people on social media earnestly telling you how bad everything is now, and if only we could return to the lifestyles of 13th century peasants then things would be good again. The story of light bulbs is a tiny counterpoint to that, and along with vaccines, food supply, nuclear and renewable power and all the rest of it, contributes to my sense that despite the many problems of the 21st century, technological and scientific progress will be our route out of it.

But there’s something else important in terms of solutions as well. People often advocate particular ways to solve one aspect of a problem without considering things like second-order effects and opportunity costs.

In a vacuum, it may well have been the right thing to push for compact fluorescents and to subsidise their implementation. But a decision based only on comparing those bulbs and their predecessors misses an important part of the story. By artificially lowering the price of compact fluorescents, the tipping point at which LEDs could take over was moved later. And because of the longevity of the fluorescent bulbs, people will still be running some of them now, despite the fact that replacing them straight away with an LED would reduce energy bills and carbon emissions.

The compact fluorescent story is only one example of this. Another classic example (coincidentally or not, from around the same time) was the UK’s move to subsidise diesel cars on the grounds of carbon efficiency, without properly factoring in the effect this might have on air quality in cities.1

From the point of view of good government based on solid scientific evidence, this kind of thing can have a corrosive effect on public trust. You can’t blame someone who followed Government advice and bought a diesel car in 2010 for being annoyed if they now can’t drive it into a city without paying a hefty surcharge.

In the same way, it’s hard not to raise an eyebrow at the fact that while we were being told to wear one- or two-layer cloth masks against COVID in summer 2020, officials2 were privately writing that they thought this was ineffective:

For me, this emphasises the importance of Government and scientists accurately calibrating the uncertainty about the data and the evidence for the effect of interventions that they propose. The more times we discover that we have not been told the whole story, the less likely we are to trust future messages.

Further, I think the whole compact fluorescent story is a good reminder that solutions need to be effective and simple, in order to keep the messaging around them clean. You can’t expect most people to read up on the different types of lightbulbs, and in other settings if you start simultaneously advocating for lots of different solutions at the same time then it’s easy for people to get confused about which ones matter most.

For this reason, I’m somewhat in despair when I read people on Twitter advocating that ordinary citizens in the West should now be wearing masks to prevent the spread of H5N1 and mpox. For a start, with everything we know about the current levels of infection, it’s very unlikely that anyone (outside those in a few specialised jobs) will come into contact with this virus at the moment, so at best it’s likely to be a placebo for a while.

I wrote in April 2023 about the possible harms in terms of messaging fatigue and timing of waves that could arise from Independent SAGE members advocating for masks to stop the Arcturus wave3 and I think similar things apply here too. Just as with compact fluorescents, advocating for a wrong or mistimed solution isn’t cost free.

It would be easy for someone in the West wearing a mask against mpox to decide that they are protected and have done their bit, and to downplay the importance of the measures that real mpox experts like

argue for here:In that sense, it feels to me like any reaction to mpox which doesn’t have at front and centre “listening to people on the ground, stepping up the manufacture of vaccines and getting them to Africa as cheaply as possible” is likely to be yet another well-intentioned decision that we look back on with regret in the future.

Thanks, Independent SAGE founder David King.

Remember that one? Me neither.

Illuminating! I had literally not known until I read this that LEDs were a different technology from compact fluorescents, but it does explain a lot. My dad (who is not usually grouchy or change-resistant, but is a die-hard fan of the Big Light in the Living Room) absolutely HATED compact fluorescents because of the dimness when you first switched them on. He drove around every specialist lighting shop in south west London and bought up all the incandescent bulbs he could find — I suspect he’s still got some. He’s probably emitted several excess kilotonnes of carbon through this alone.

Great post although I feel like westerners masking up for mpox is a bit of an easy target. I would be interested to hear your thoughts on a more contested topic - for instance banning smartphones for under-13s. Would you apply the same logic there or is this a time for the precautionary principle?