Qualified immunity

Did all the extra credit, then got graded on a curve

Sorry, it’s been three weeks since I last sent out a newsletter. I’ve been busy with various things - in particular I’m excited about my getting a new job, but the interviews and preparation took a lot of time and thought, as well as trying to get on with teaching, research and everything else.

Of course in the meantime the COVID Inquiry has been rumbling along, taking up a lot of column inches and going over and over the same ground from a wide collection of viewpoints in Rashomon style. This week saw appearances from both Patrick Vallance and Chris Whitty, who I thought both emerged with a lot of credit for their willingness to reflect honestly on their decision-making at the time.

I should mention, by the way, that Vallance is the only one of the COVID main players who I’ve met in real life. He chaired a panel that I was on at the Royal Society in June 2022, and I was extremely impressed with him then too. This was the time of the BA.5 wave, when admissions were climbing at an uncomfortable rate towards potentially unpleasant levels. We’d been told that the panel needed to run to time because Vallance had to get to Downing Street. In fact, he did hang around at the end, to take the time to talk to relatively junior scientists who had delayed their PhDs and postdocs to work on the COVID response, and to offer to provide reference letters to employers putting that sacrifice in context. I don’t know about you, but that feels like the kind of person I’d want in charge in a once-in-a-generation scientific crisis.

Heebie-GBs

Anyway, the Inquiry has continued. A lot of the discussion has revolved around herd immunity and the Great Barrington Declaration. Unfortunately I’m not convinced that a lot of this has been very useful, so I thought I’d put on my flameproof underwear and say something about it here.

The first thing to say is that I am not in any sense a Great Barrington supporter. I didn’t sign it at the time, nor would I have done on reflection. But equally, I don’t like the way that it seems to have become a strawman to beat up on, often when making wild accusations of eugenics, because I think the discussion deserves better than that.

On some level, it’s not a crazy idea. From standard epidemiological models, we would expect that when around 60% of the population had achieved immunity from the original Wuhan strain of the virus the R number would be forced under 1 and the epidemic would start to shrink exponentially. This is the famous herd immunity threshold.

Given that it was long known that severity was highly age-dependent, in the absence of a vaccine it makes sense to get those 60% of infections among the less vulnerable sections of the population. Indeed it was an explicit part of the UK’s official strategy that even before full legal lockdown those at risk were encouraged to take extra measures to protect themselves, which would steer infections towards other groups.

However, in my view, the problems with the Great Barrington Declaration are in terms of implementation as much as anything. While the idea that (as it said)

The most compassionate approach that balances the risks and benefits of reaching herd immunity, is to allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk

sounds attractive, it’s not entirely obvious how this could be achieved in practice. For example the GBD stated that

By way of example, nursing homes should use staff with acquired immunity and perform frequent testing of other staff and all visitors.

But this document was published on October 5th 2020. At that stage it’s likely that only around 10-15% of the population had immunity, so it would have required a huge amount of upheaval and training to suddenly catapult many of those people into nursing home roles (even if they’d wanted them) and to find new roles for 85-90% of non-immune care home staff. Worse, immunity wasn’t homogeneously distributed across the country, so we might well have had to temporarily relocate people from London boroughs to the South West for example.

Similarly, “frequent testing” wasn’t really an option at this stage. We were doing around 300,000 tests a day, across the UK. This might sound a lot, but only represents a small fraction of the population. Even if we didn’t use any tests at all for people who were actually sick, it wouldn’t achieve anything close to daily coverage of 750k workers and 440k residents in care homes, let alone 1.3m people working in the NHS who we’d presumably also need to monitor in a similar way.

Further, only having PCR tests meant that the results were only available a few days later, by which stage they were less useful - at best they could only offer retrospective information. Four or five months later, when lateral flow tests were widely available, this kind of testing strategy became more possible, but at the time of the GBD we were severely constrained by test capacity.

Beyond that, I think there’s a less-discussed problem with the idea of obtaining focused protection in this way. That is, 60% immunity might be the figure to prevent spread in a well-mixed population, but that was far from what we were seeing at the time. Imagine a care home full of so-far uninfected people: if the virus did get in, then having 60% immunity in the general population wouldn’t stop it sweeping through once it was inside.

Perhaps prevalence in the outside world would be lower as a result of general immunity, making this scenario less likely, but reaching herd immunity doesn’t mean eradication. Indeed with what we know about reinfections, until the vaccine arrived to mitigate the worst effects for their residents care homes and similar venues would have remained vulnerable, and constant vigilance against outbreaks would have been required in the long term.

Following the herd

But then, if Great Barrington wasn’t feasible, then what was the policy? A lot of weight has been placed on Patrick Vallance’s Today programme interview of 13th March 2020, when he said:

Our aim is to try and reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely; also, because the vast majority of people get a mild illness, to build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission, at the same time we protect those who are most vulnerable to it1. Those are the key things we need to do.

This statement has been interpreted to mean that the UK strategy at that stage was simply to ‘let it rip’, to try to reach the 60% infections (or whatever it would be) in one go. Clearly, this wouldn’t have been a great idea if the kind of protection he mentioned wasn’t possible. It’s not a hard sum to work out that 60% of 67 million people makes about 40 million infections, so if these were evenly distributed by age then a rough IFR of 0.7% would mean something like 280k deaths to achieve herd immunity. (We’ve still only seen 233k, despite the arrival of the more severe alpha strain).

In fact it’s likely to have been worse than that. That many infections in one wave would presumably have led to a very high peak, where hospital services could well have collapsed, and so the 0.7% figure would likely have grown considerably as oxygen and treatment were not available to all who needed it. Further, there would have been a sizeable overshoot - the herd immunity threshold only comes at the peak of the epidemic not its end, and many more people (perhaps of the order of a third as many again) would have died on the downslope after that.

But of course, Patrick Vallance would have known that - he’d been thinking about this stuff for months. Personally, I think it’s likely that he simply misspoke. He was facing a degree of daily pressure that most of us can hardly imagine, and was under the stress of doing a live interview. I think it’s most likely that he meant to say “some kind of immunity”, not what he did say. (If nothing else, herd immunity is really a binary “yes or no” kind of concept, so it doesn’t make sense to talk about “some kind of herd immunity”). Indeed in his subsequent witness statement, he has tried to walk back this interview, and it seems fairly uncharitable to imagine that he was accidentally letting slip the true strategy.

Indeed, the idea that we might want to get “some kind of immunity” was presumably the plan, or we would have locked down very early in March. It was clear from SAGE modelling that if we suppressed the first wave completely, then we risked a bigger second wave arising in winter when other pressures on the NHS would be worse. Indeed, the SAGE meeting of the same day (13th March) was agreed:

SAGE was unanimous that measures seeking to completely suppress spread of COVID-19 will cause a second peak.

I’ve argued before that estimating the growth rate wrongly may have led to the degree of immunity gained in the first wave (or rather the number of deaths that resulted) being larger than anticipated, and it’s good to see the Inquiry and journalists pursuing that issue. However that doesn’t imply that the strategy itself was not broadly sensible.

In fact, I think it’s even possible to roughly quantify what the second wave might have looked like otherwise. If we suppose that we hadn’t gained 10% immunity in the first wave, then it’s reasonable to imagine (from the same kind of standard models) that the second wave would have grown 10% faster per five day generation. On a logarithmic scale, this just leads to steeper straight line growth (blue) than we actually saw (red), but the difference may not look so significant.

But the remorseless logic of exponential compounding means that on a linear scale, the wave would have been visibly much more severe than it actually was. This would have presumably forced us to take heavier measures even earlier in the autumn, as the crisis got worse faster and the levers that we tried to pull on had less effect.

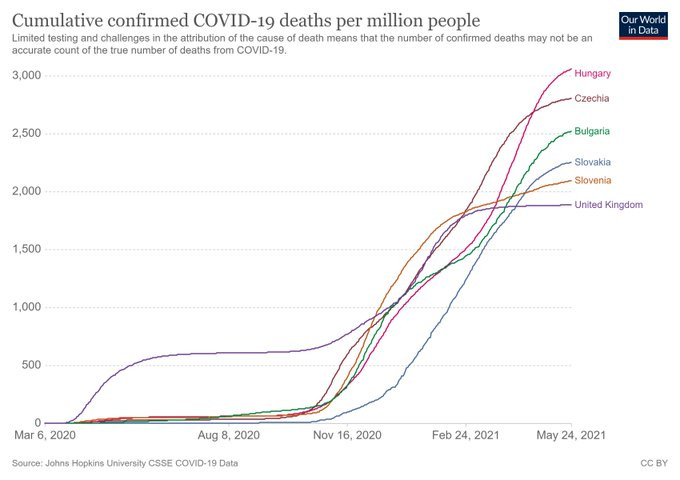

If this seems like a fanciful mathematical game, it’s worth remembering that this is more or less exactly what we saw in Eastern European countries - many of whom succeeded in suppressing the first wave, but ended up with a worse overall outcome than the UK in the end.

Stuck in the middle with you

So, having explained why I’m not convinced that either Great Barrington or complete suppression could have worked, I was amused to see that Chris Whitty’s witness statement also explicitly advocated the kind of “corona centrist” approach that I have often argued for.

In the end, of course immunity is important and was the only way that the pandemic was going to end. So perhaps the most important story had taken place a month before, when an Oxford University press release had described plans to manufacture the first 1,000 doses of a new vaccine for clinical trials.

But in terms of the Inquiry learning the right lessons from the pandemic, it might be prudent to at least consider what the right strategy might have been had the vaccine not arrived in time. Could widespread use of lateral flow tests have prevented the kind of multi-year on-off cycle of restrictions modelled in the original Imperial Report 9, for example? Hopefully we might get answers to some of these questions at some stage.

You’ll notice that the sensible part of the GBD, that we should try to keep infections away from vulnerable people as best we can, is here already.

Excellent as always, thank you. One of the clearest explanations for Vallance’s statement that I’ve read. He was brilliant with journalists throughout, despite what must have been intense provocation. We had weekly briefings which were meant to be off the record yet somehow ended up being reported yet he patiently kept on explaining

Excellent, clear write-up. Thank you very much. And congratulations on the new job.