The Edge is Everything

You win some, lose some, it's all the same to me

Happy New Year - I hope 2024 is a wonderful year for you! You might be thinking about resolutions and reboots: setting yourself targets to go to the gym three times every week, or to permanently change your diet and lifestyle in other ways. Of course, I hope you manage this, but I’ve been thinking a little bit about the pursuit of perfection, and whether embracing “failure” can actually be a healthy thing.

It’s all prompted by watching The Edge of Everything, Amazon Prime’s documentary about the snooker player Ronnie O’Sullivan. I’m not a huge snooker fan - like a lot of people, I’ll watch some of the World Championships on television in the spring, but I’m not exactly following every tournament the rest of the time. Nonetheless, I found this film extremely compelling, with O’Sullivan giving an honest view of his struggles with his mental health and with the game.

But as someone who works with probability I found it hard not to see it as a film about a man fighting against the inexorable effects of randomness itself. O’Sullivan is undoubtedly a great player, probably the greatest ever. His record contains more tournament wins, more century breaks and more 147 breaks than any other player, so it might be tempting to conclude that he is unbeatable. And of course if you or I stepped up to play him, we’d probably feel satisfied if we managed to pot a single ball.

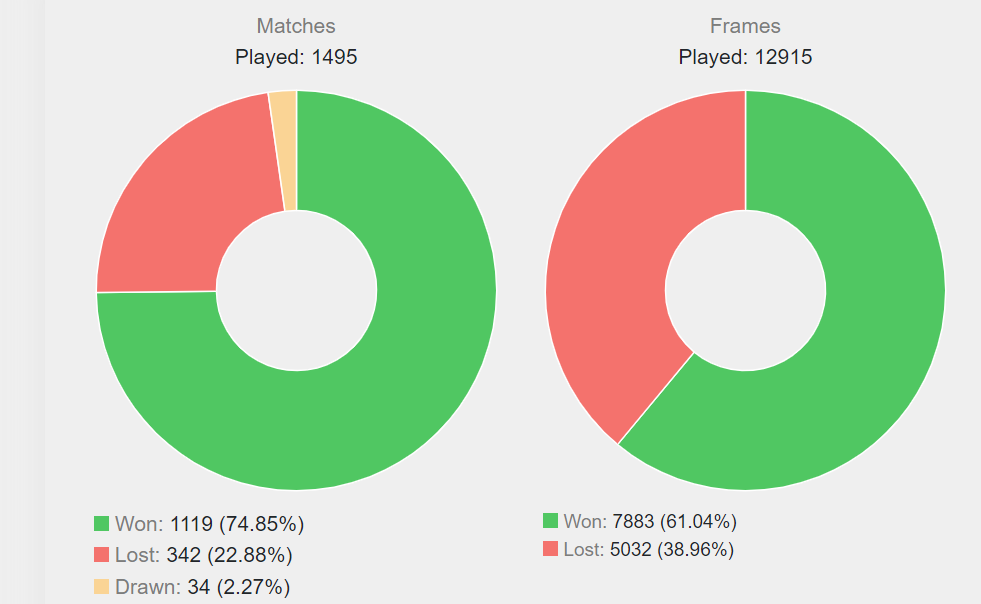

However, what proportion of his frames do you think O’Sullivan wins? Well, according to the website cuetracker.net, the answer is 61%.

Perhaps thinking about it, that isn’t surprising. Early in the film Stephen Hendry, the most credible alternative candidate for “greatest player ever” explains just how hard snooker is, as a game of precision. There are tiny margins involved and errors compound themselves rapidly when trying to build a break. If in the course of potting the first ball, the cue ball hits the red a tiny fraction from where you intend, it may end up millimetres away from where you intended, making the next shot harder. This makes it more likely the cue ball will end up centimetres away when you pot the colour, and the whole thing starts to spiral out of control. And that’s just potting two balls in a row, let alone the thirty-six required to score 147.

In that sense, the fact that O’Sullivan has completed fifteen maximum breaks in his career can perhaps be seen as a miracle. (It wasn’t until 1982 that anyone at all managed a single 147 break in a professional tournament). But in fact, it’s harder than that. O’Sullivan isn’t just playing on his own, he’s up against other good and great players, each of whom also has the potential to perform similar miracles.

One of my favourite scientific essays is Stephen Jay Gould’s article about the disappearance of .400 hitters in baseball. Gould argues that no player has achieved this outstanding feat since 1941 (whereas it was much more common before that), not because the standard has got worse but because it has got better. If the overall quality of pitching and fielding rises, perhaps as the talent pool grows or training methods become better, it becomes harder for any one player to be truly dominant. And it’s convincing that standards are high in professional snooker - as Wikipedia tells us:

Only eight recognised maximums were achieved in professional competition in the 1980s, but 26 occurred in the 1990s, 35 in the 2000s, and 86 in the 2010s.

We can see these kind of effects in other sports as well - take football for example. In the last six-and-a-half years, Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City have put together a good claim to be the greatest team ever. With a fantastic manager, access to the world’s best players, huge squad depth and of course question marks over their financial domination, they’ve won five out of the last six Premier League titles. But in that time, they’ve actually “only” won 185 out of 246 league games. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a remarkable record of consistent excellence. But it’s certainly not the case that they automatically win every game: in fact, it doesn’t happen one time in four.

In that sense, O’Sullivan’s 61 per cent frame record is pretty impressive. While World Championship games are longer, a lot of his tournament games will be the best of 9 or 11 frames. This edge in frames converts into a bigger effect in terms of matches. If we consider a simple model that every one of O’Sullivan’s frames is just an independent biased coin flip, with a 61 per cent chance of coming up heads, then these are the probabilities of him winning different numbers of frames out of 11 (ignore the fact that the match stops when someone gets to 6, imagine that the frames get played anyway):

You can see there’s a good chance he ends up ahead - in fact he’d win 77.5% of his matches. But still, like Manchester City, a quarter of the time O’Sullivan wouldn’t win the match - which is more or less exactly what we see in his career record in the cuetracker pie chart above. And unlike Manchester City in the league, if he loses then he is eliminated from the tournament - it’s unbelievably tough!

For example, consider a very dominant player who wins 75% of his matches. To win the World Championship, he still has to win five matches in a row: that will only happen (3/4)^5, or 24% of the time. In that sense, O’Sullivan’s 7 World Championship wins out of 31 Crucible appearances are more or less exactly what you’d expect. It’s tempting to focus on all the years he didn’t win the world title: and parts of the film see him trying to come to terms with that. But really, on some level he’s just fighting against randomness.

In fact, I think you can view O’Sullivan as a casino player with an edge over the house. On average he’ll come out ahead, but this is far from guaranteed. All he can hope to do is to maintain or improve that edge, bearing in mind that it’s a very small one relative to his peers. For example, the same website tells me that four-time World Champion John Higgins has won 59% of his frames and 69% of his matches. O’Sullivan’s record is better, but only just. Over the course of a tournament, it’s very possible that Higgins will win more frames than him, and there will be thirty-one other very good players facing him at the Crucible.

So, in terms of lessons for ordinary mortals thinking about our New Year Resolutions, I think it’s good to be ambitious, but you shouldn’t be too hard on yourself. Whatever you promise yourself now, there will undoubtedly be weeks when you don’t get to the gym three times because you are ill or have a crisis at work or home. But that doesn’t mean that the ambition was useless and you should give up on it. In my view, it’s better to notch up the wins you can, to stay ahead on average, to build your edge, rather than to have an “all or nothing” attitude that focuses too much on your failures.

Anyway, Happy New Year again - and I look forward to writing more here in 2024 (but make no unsustainable promises about how often!).

In Novak Djokovic's utterly dominant calendar year 2015, in which he won three Grand Slams and lost in the final of the other, he won just 56.1% of his points in slams. (Source: https://www.tennisabstract.com/cgi-bin/player-classic.cgi?p=NovakDjokovic&f=A2015qqC2 )

Rahul Dravid one of the greatest batsman ever, once said - 'I batted 604 times for India. I didn't cross 50 runs 410 times out of those innings. I failed a lot more than I succeeded. I'm more a failure than a success. I'm quite qualified to talk about failure'