There we are again in the middle of the night

As I tweeted a month ago and wrote here a couple of weeks ago, we’ve moved into the next chapter of the COVID story, as a new faster-growing variant, JN.1, has emerged from the BA.2.86 family. BA.2.86 itself first emerged in August and, despite initial predictions of rapid doom, turned out to not be too much of a big deal. However, as the Cyrus family illustrates, children don’t always end up like their parents, and while BA.2.86 was more in the “mildly irritating” category it may feel like JN.1 could be more of a wrecking ball.

So far, things are working out more or less as a simple model based on variant percentages might suggest. The dashboard shows that UK COVID hospital admissions returned into growth over the last two weeks. While the numbers are currently pretty low for this time of year by historic standards, there is an obvious concern.

That is, a relatively small (10%) increase in the first week of growth was followed by a larger (27%) one the week after. So, this isn’t a scenario of simple exponential growth, where the numbers get multiplied by the same factor each week. Rather, like a bank loan where the interest rate is getting higher over time, the models suggest that as the percentage of JN.1 increases the overall growth rate itself will grow over time. That’s not good news!

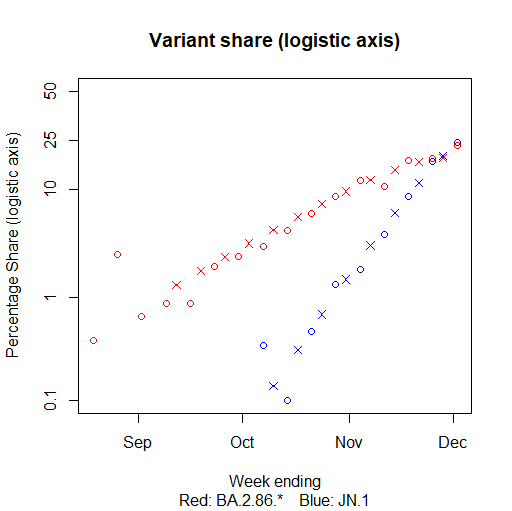

In fact, I can illustrate this with a simple toy model which I tweeted the other day. If I imagine there are essentially three types of variant, namely JN.1, BA.2.86 and “everything else”, and estimate their respective growth rates, then I can come up with something which fits pretty well to observed data. For example the true (circles) and modelled (crosses) percentages of JN.1 (blue) and BA.2.86 (red) seem pretty close:

Further, this converts fairly well into a simple model for hospital admissions data, where true (circles) and modelled (crosses) values lie close together.

On one hand, you shouldn’t be so impressed to see a fit to existing data (remember von Neumann’s elephant - and these processes are probably simpler than any elephant!). But, even though I’d tweeted it a few days before, it didn’t do a terrible job of predicting this week’s daily hospital admissions data either. Under this model:

this week wouldn't be so bad (350), but then 460 and 690 isn't so great.

In fact the true figure this week was 375 (this is a seven-day average of the most recent week’s data). So, not bang on, but not an awful guesstimate either (remember there’s a certain amount of randomness in the observed data1), and perhaps close enough to take the model vaguely seriously for now.

And in fact, the model numbers get progressively worse pretty fast: in successive weeks it suggests 1140, 1990, 3600 and 6670 daily admissions. In other words, in six weeks from now if we followed these trends we’d exceed even the January 2021 admissions peak that led to lockdown. This seems like it justifies some of the alarmist messages being heard about JN.1.

But it’s important to say: I don’t believe those numbers for a second.

We're all here, the lights and noise are blinding

To understand why, we need to go back to thinking about absolute and relative growth, and thinking not just about variants but also about mixing.

In 2020, to understand the likely trends it was necessary to fixate on restrictions on social contact. People spent hours wondering if opening hair salons and gyms would take the R number up over 1. The reason for this was that (until the arrival of alpha), the COVID strains circulating had fairly similar intrinsic growth rates, and since immunity was low, the effect of mixing was dominant.

However, at least since the winter 2021 arrival of omicron the dynamic has felt much more variant-driven. Mixing is generally fairly constant now that everything is open, but we’ve seen successive wave(let)s associated with new variants having a competitive advantage relative to the circulating strains of the time. (Of course many variants also arrive with no real advantage, but by definition we don’t need to worry about them).

So, my simple model just assumes that the three strains have a constant exponential growth rate2 in absolute terms: that JN.1 is going up 90% per week, BA.2.86 is going up 15%, and "everything else” is decaying by 16%. These numbers aren’t perfect by any means, and I didn’t spend hours fitting them, but they are good enough for illustrative purposes.

But in figuring out what comes next, I think we need to return to a bit of a 2020 mindset. That is, it’s December! Pubs and restaurants are crowded in the run-up to Christmas. Lots of people are packed together at office parties. Halls full of parents and children have been watching nativity plays. And that’s great.

It’s no coincidence that we’ve developed these social rituals to get us through the darkest and most miserable time of the year. Of course, from an infection control point of view, it would be better if I hadn’t been to two work parties last week. But from any other point of view, I’m delighted that I did. As Anthony Bourdain wrote in Kitchen Confidential:

I may be perfectly willing to try the grilled lobster at an open-air barbecue shack in the Caribbean, where the refrigeration is dubious and I can see with my own eyes the flies buzzing around the grill (I mean, how often am I in the Caribbean? I want to make the most of it!), but on home turf, with the daily business of eating in restaurants, there are some definite dos and don'ts I've chosen to live by.

In other words, I believe these occasions are the equivalent of Bourdain’s Caribbean lobster (a chance to be seized), because I know how quiet January is likely to be in comparison. Restaurants where you previously had no chance of a table will now be luring you into empty spaces with 2-for-1 offers. December pub goers will have turned into Dry January advocates, letting their livers and bank balances take a break. December and January look very different, socially. And while Christmas itself tends to see families getting together, the period immediately after is typically quiet.

Hold on to the memories, they will hold on to you

From the point of view of understanding future COVID trends, it’s absolutely vital to understand this. It’s perhaps hard to quantify the effect, but we can take a stab at it, based on last year’s data. Then the situation was simpler because we only had a single variant, and we can see how growth went into reverse over New Year.

In the weeks running up to Christmas 2022, there was again a wave (caused by BQ.1). The last two weeks before the holiday saw a 36% and 28% weekly growth in admissions. But into the New Year, the direction changed, and we saw 17% and 21% falls. Of course, some of this reversal may have been caused by growing immunity. But I think it’s possible to understand it in terms of reductions in contacts.

If we imagine that a 30% pre-Christmas growth rate converted into a 20% January fall, that’s roughly a 40% drop in the weekly COVID growth rate (1.3/0.8 is 0.61). That seems pretty steep, but actually isn’t off the table because the short omicron infection times which I wrote about last week lead to very volatile trends. For example a 15% decrease in contacts, compounded across three generations per week, would lead to a fall in growth rate of 0.85^3 = 0.61 - exactly the drop observed. Personally, I don’t think it’s crazy to think that you might have 15% fewer social contacts in January than December, so this effect might seem about the right size?

This sum doesn’t need to be perfect, of course, but it’s worth considering the size of this effect when applied to the toy model I mentioned before. We can consider reducing each of the individual weekly growth rates by the same 40% factor seen last year. The “everything else” which was falling 16% per week would now be dropping like a stone (halving weekly). BA.2.86, previously growing by 15% per week would go into reverse and fall 30%/week. That’s not bad at all!

Even JN.1 would go from a weekly absolute growth rate of 90%, apparently driving inexorable fast exponential growth, to only 15%. Since by that stage JN.1 would be the dominant variant, my sense is that we would probably just about still be in overall growth (remember that the total growth rate is the weighted average of the individual growth rates), but nothing like as fast as before. While the relative advantages might roughly persist, in absolute terms the picture would be very different.

There’s probably quite a margin of error on this (the 90% and 40% figures were both pulled somewhat out of nowhere, and may not be accurate) in terms of whether January sees slow growth, a plateau or even a fall. But it seems to me highly plausible that, since December levels of mixing are likely to drop off, so too are the overall growth rates. We shouldn’t extrapolate admissions trends into January based on the behaviour of JN.1 in party season.

It’s hard to be sure exactly when things might start to change, given lags from infection to hospitalization, but since the next two weeks’ reports of data should cover admissions up to 15th and 22nd December I personally wouldn’t feel confident extrapolating the trends much beyond that. In which case, if we do believe that contacts will become lower from around that point onwards, then it perhaps seems plausible that we might perhaps be looking at daily January admissions numbers closer to 1,000 than to the 2,000 or so previously seen at the peaks of the BA.1, .2 and .5 waves.

Of course, that’s still not ideal. As

continues to convincingly argue, the NHS is under great pressure already. Adding a COVID admissions wave of this size into an already struggling system (which may also be dealing with the effects of a likely flu wave and junior doctors’ strikes across the same time) is definitely not good news. But equally, even based on the current observed steep growth rate of JN.1, anything approaching a 2020 or 2021 level outcome seems unlikely to me right now.In the meantime, it might be worth taking individual small steps to moderate the behaviour of these graphs. If you’ve got symptoms, it would be worth trying not to pass your bug on, if you can - particularly bearing in mind the risks of intergenerational infections. If you are able to get one, then a COVID or flu jab seems well worth it. And while I’ve been sceptical of past calls to return to general masking, I could see an argument for offering masks in healthcare settings for a few weeks around the peak to reduce some of these NHS pressures.

Of course, this is all just one attempt at looking at the tea leaves, and as I constantly say, over-confidence about anything COVID-related is usually a sign that you’re heading for a fall. So things could easily work out better or worse than I describe here. But regardless, do have a great Christmas, thank you for reading this Substack in 2023, and I look forward to telling you soon about some public lectures that I’m giving in 2024.

I don’t think the randomness is big enough for me to argue that I was morally right, but it’s not a million miles off.

Yes, I know this isn’t correct. Nothing grows exponentially forever, but things can grow roughly exponentially for “long enough”.

Thank you for your post, as ever. Is there a way from this data, and from other data sets, for you to estimate how many people may have Covid in the UK right now, and what the chances of an “average” person catching it in the next few weeks might be?

Thank you for an extremely clear, accessible and (mildly) reassuring explanation of the current situation. It is all feeling a bit too 2021 for my liking.