It’s January 2024. You’re a politician, and a lobbying group hands you a leaflet reading “COVID Infection Fatality Rate 0.66% (The Lancet)”. You’d be pretty worried, I think.

But then, you (or a numerate member of your team!) do some sums: you know the UKHSA/ONS survey estimated that on 13th December 2.5 million people in England and Scotland had COVID. So, if that fatality rate was right, you’d expect to see 16,500 resulting COVID deaths in about a ten day period, or 1,650 per day1. You open the UKHSA dashboard on your phone, and see that the latest daily average is 30.

How would you react? You might well decide this must all be nonsense, throw the leaflet away, and ignore whatever else it had to say.

However the Lancet number is correct, in a sense - but it was a 2020 number, and vaccines and immunity have changed the game. My contention is that similar unhelpful things happen in the world of Long COVID advocacy. So I’d like to annoy everyone by arguing that a) Long COVID isn’t anything like the problem it was b) long haulers have been let down c) no, it’s not a way of hiding vaccine injuries.

Operation Moonshot

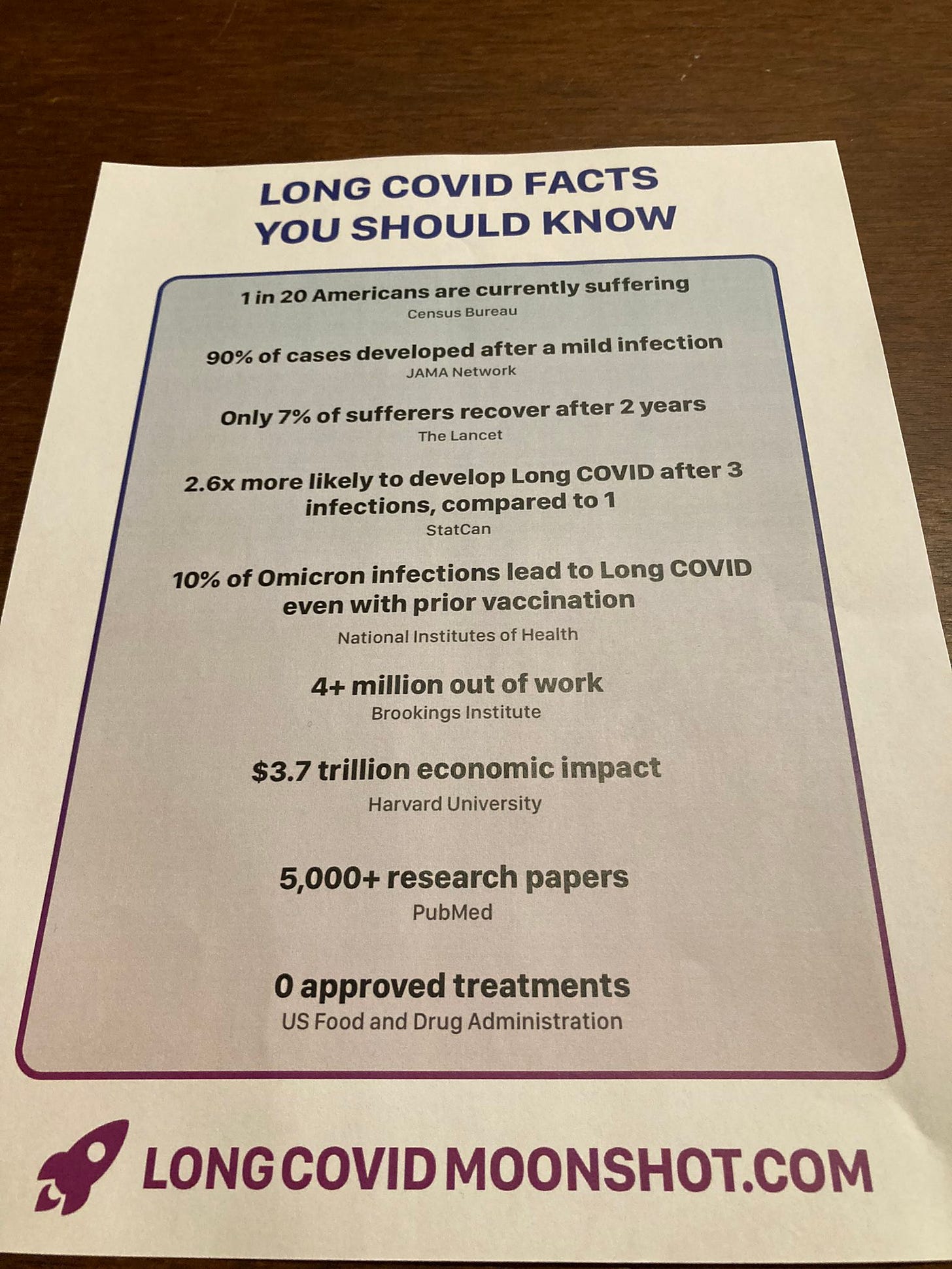

These thoughts were prompted by this leaflet being handed out at a US Senate hearing chaired by Bernie Sanders. I think a similar analysis shows that the top five facts can’t be simultaneously true - and this risks distracting from the final point, which actually shows that the situation really isn’t good enough.

Of course, we don’t know for sure how many infections there have been recently. But Michael Fuhrer, who I trust as a numbers-based COVID realist, estimates from wastewater data that there were about 1.6 omicron infections per person in the United States during 2022-3. So, if 10% of those lead to Long COVID as we are told2 then 16% of the population would suffer at some point. And if 93% of such cases don’t resolve in 2 years, that would leave 15% of the population currently suffering due to omicron infections alone (even ignoring long haulers with pre-omicron Long COVID), three times the “1 in 20” from census data.

Clearly something is wrong. While not official, the estimate of 1.6 infections each in that time seems consistent with the cumulative incidence calculations performed by Abbott and Funk based on randomly-sampled UK ONS data in the same period, so I don’t think it’s that.

The claimed Census data also seems solid: the most recent figure from the Household Pulse survey (run in partnership with the Census Office) is 5.3% of Americans suffering from Long COVID in October 20233, so I’m happy to take that as correct too. In fact, this Household Pulse dataset helps clarify matters somewhat. The first reported “currently suffering” figure was 7.5% in June 2022. So, even if no new Long COVID cases had occurred, about a third of the people listed then no longer are, which suggests that recovery is possible at a greater rate than the leaflet claims4.

More interestingly, Household Pulse also estimates how many Americans have ever had Long COVID. Of course, this number should only ever go up, but (perhaps for statistical sampling reasons) it doesn’t always. However, the June 2022 figure was 14%, and the highest ever figure was 15.7% a year later. But this extra 1.7% is a far lower rate of new cases than my calculations based on the leaflet suggest.5

In fact I believe the 10% current conversion figure is suspect. This isn’t just me going on vibes. Since most infections will be reinfections these days, I expect the true figure would be closer to the 1.6% for adults and 0.4% for children estimated for reinfections in the omicron era by the ONS in 2023.

, no Long COVID minimiser, suggests that something like 2% might be the true overall figure (though rightly points out this will vary by individual circumstances). But these are all a lot lower than the 10% quoted.This perhaps shouldn’t be a huge surprise:

has convincingly arguedthat Long COVID is strongly correlated with severity of infection. And since lower death and hospitalization rates per infection show that severity is generally lower now, we shouldn’t be surprised to see a lower incidence of Long COVID per infection in 2024 than in 2020. Judging from the reduced hospitalization rates from the JN.1 wave, even the 2023 ONS 1.6% and 0.4% figures might be too high now.

So, are we done? Sadly, not at all.

In for the long haul

Just because new infections might not be turning into Long COVID cases at the rate they did, it doesn’t mean there’s not a problem. Indeed, I feel that it’s unfortunate that the amount of time spent arguing about the 10% figure and the Russian roulette model can hide the more important issue.

I think the key here is the 7% recovery figure. Like the Lancet number I quoted above, it’s real. That may seem confusing, because I just said it didn’t match the Household Pulse data! But the issue is that too much of the discussion tries to conflate Long COVID of different severities into a single number. Clearly, “still having a cough at 5 weeks” and “being unable to get out of bed after 2 years” are not comparable in effect, and presenting aggregate figures and looking at overall recovery rates averaged across both can mask the seriousness of the latter. And of course it makes perfect sense that more severe Long COVID cases are harder to recover from.

While I can’t be sure, my understanding is that this is the paper referred to: here only 7.6% of the cohort recovered from Long COVID within 2 years. But the key is the first sentence of the Methods section:

This was an observational prospective cohort study of COVID-19 survivors who visited the Long COVID Unit

This isn’t representative data for the whole population! These are the people who had Long COVID the worst - the ones suffering enough to get referred to a specialist unit. So, having dug a little, it’s easy to feel this isn’t relevant to the whole population (as the leaflet implies) and that’s probably reasonable.

But that doesn’t mean that there’s not a problem! I’ve argued that omicron infections may not be converting into Long COVID at the previous rate, and that many people do recover from the milder forms of it. But that in no way reduces the fact that, as this paper suggests, the smaller group of long-haulers with the most serious symptoms (many with infections originating right back in the first wave) may not be getting better anything like as fast as we’d hope.

The data from the last ONS Long COVID prevalence survey is slightly inconclusive, and any new numbers from the rebooted ONS COVID prevalence survey might help us drill down further. But for me, the key figure there isn’t the headline 1.9 million with Long COVID of any severity. It’s the 545k people first infected in 2020 (before alpha), and the 381k whose activity was limited a lot. There are caveats here (someone having post-acute symptoms after reinfection may be counted in the first category for example), but it’s entirely plausible to me that there is a sizeable intersection between these numbers.

Whatever the risks in the omicron era, it would be wrong to ignore the strong likelihood that there are hundreds of thousands of UK people (and presumably a comparable proportion of the population across many Western countries as a whole) who have suffered from serious forms of Long COVID for three years or more. So if I was advising the advocacy groups (and I know they don’t want my advice!), those people would be my complete focus, not claiming high current conversion rates. Of course, advocates don’t ignore these long-haulers completely, but mine seems a much better strategy than describing the current risks in ways that don’t match most peoples’ current experience.

I think it would be far easier to sell to the general public that people sick for a long time are being let down by a lack of treatment and research and deserve better, than over-emphasizing current infections - which can sometimes appear like a call to re-enforce NPIs on a population with little appetite for them in this low-severity period. Of course, if research did succeed then that would also help more recent sufferers too, as well as the long-haulers.

Taking a jab

Finally, as promised, I want to briefly mention claims that Long COVID is simply a form of vaccine damage. Such ideas crop up with monotonous regularity on Twitter, and I believe they are simply an attempt to derail serious discussion. In particular, since (as I have argued) a large proportion of the most significant Long COVID cases date back to the early days of the pandemic, it should be clear that most of them must have occurred in unvaccinated people.

Indeed, this can be made clear from an examination of the very first ONS report on Long COVID prevalence, which referred to ongoing symptoms for 4 weeks or more in the week ending 6th March 2021. Thus, this refers to infections before the end of January 2021, a time at which very few under-70s had been vaccinated.

Despite this, Long COVID was clearly already a serious problem: perhaps not quite on the scale of the latest figures, but already 1.1 million people were affected, 196k with their day-to-day activities affected a lot.6 Clearly, it makes no sense that this can have been vaccine damage in a group that for the most part had not been vaccinated.

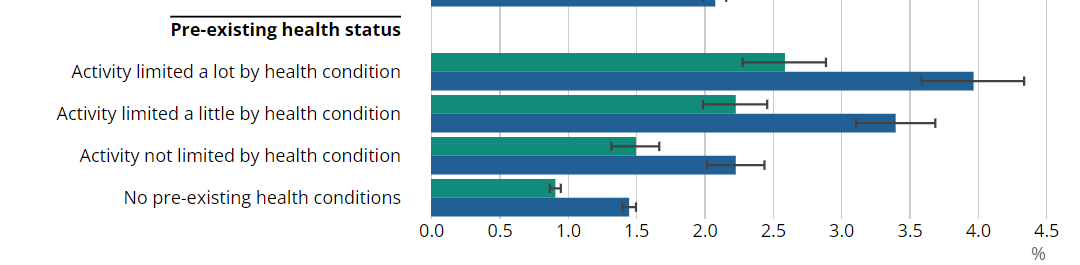

Indeed the demographic breakdown shows prevalence was significantly lower in the 70+ age group (who had been partly vaccinated by then) than in the 50-69s (who had not). Further, the graphs show a gradient by social class, with the groups typically more able to work from home less affected by Long COVID than those whose roles placed them at greater risk of infection (see also here).

This shows that as you’d expect Long COVID was strongly correlated with infection risk, and higher rates in groups with pre-existing health conditions reinforce the point made by

about severity of infection.Overall then, for me the data implies that pre-vaccination infections, which tended to be more severe, were more likely to lead to serious cases of Long COVID which take a long time to recover from. It’s hard to argue based on all the numbers that the vaccines have had any effect other than lowering the rates of Long COVID.

While we are thankfully in a position where lower severity is likely leading to a lower rate of Long COVID than before, it’s absolutely right that we shouldn’t ignore the suffering of the long-haulers and should be funding further research into these types of conditions. In that sense, I’m at least partly on board with the Moonshot leaflet, but I just wish they’d make their case differently.

Remember the 2.5 million figure is prevalence - all the people infected at one time - whereas the daily deaths figure is more like an incidence number - new daily events. So if for example you imagine that people test positive for 10 days, you can get a rough incidence figure by dividing prevalence by 10. Better methods are available.

In fact, the situation would be worse, according to the leaflet, because many of these are re-infections which we are told are worse.

You can get this data by clicking on the “select indicator” button on this site.

You can see that the incidence and recovery rates pull in opposite directions: the higher the per-infection Long COVID number, the higher the recovery rate implied by this drop.

Note also that 15.7% of people having suffered Long COVID at some stage and 5.3% having it now implies an overall recovery rate closer to two-thirds than than the one-third that I mentioned above.

As I’ve said before, this once again shows that per infection risk has fallen significantly: infections up to January 2021 represent a tiny fraction of the total number over 4 years, and yet half the current burden of Long COVID had built up in that period.

There are always anecdotes …bear with me…

1. Myself 62 vaccinated, well. First covid infection was mild mid 2023, couple of days. Subsequent fatigue lasted 7 months limiting usual activity such as walking locally and felt 10+ years older lying on the settee a lot. Would have been off work if wasn’t retired. All resolved gradually after 6 months.

2. A friend, 20s vaccinated. Post covid (2021) it took a year before he could run again due to fatigue.

3. Another friend in 60s had other physical post covid problems, but I don’t have permission to comment.

So there is severely debilitating LC and your mathematical stats review is great.

But there is also the less severely affected post covid cohort whose reduced capacity to function is significant to them. Many may not see a doctor (I had basic bloods checked eg for hypothyroidism, all ok) and hopefully most recover in time.

This should not be dismissed, the numbers must be high and the impact upon the economy and their own and other’s well being should be counted I think. I don’t know how that can be done and clearly those with severe illness need the scrutiny and treatment prioritised.

I guess at some point it will be possible and acceptable to count the milder as well as the severe and hopefully there will be less of it by then. Maybe rating scales such as with eg knee pain (does it hurt 1-5 and does it affect daily living activities 1-5 could be used) to assess.

Not for you to sort out, but I wanted to say…

Excellent analysis. My one doubt is that the ONS and Household Pulse Long COVID stats are likely overestimates. Both are, I understand, self-reported data without a control group. Some common symptoms of Long COVID have high baseline incidence and prevalence in the uninfected, particularly fatigue and breathlessness. Lack of control for the baseline would inevitably lead to an overestimate of the effect of Long COVID.

This study, in non-hospitalised and mostly unvaccinated patients pre-Omicron found about 5% incidence of Long COVID-like symptoms in the infected, vs about 4% in a matched cohort of the uninfected: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01909-w

That study is subject to its own methodological limitations. In particular, there were likely undetected infections in the control group leading to an over-estimate of the baseline incidence of symptoms. However it does illustrate the need for a well-constructed control group to separate symptoms due to Long COVID from identical symptoms occurring for other reasons.

The above argument is also made more eloquently and extensively in this article: https://ebm.bmj.com/content/early/2023/08/10/bmjebm-2023-112338