Myth busters

Bustin' makes me feel good

Someone set up us the bomb

On the 20th June 1944, Wernher von Braun’s V2 rocket became the first man-made object to travel into space. These unstoppable missiles could travel at three times the speed of sound and carry a tonne of explosive into the heart of London and, despite D-Day, the course of the war suddenly seemed uncertain.

Almost immediately, Leonard Cheshire and his 617 Squadron were called into action to try to destroy the reinforced concrete bunkers the rockets were being launched from. For three days and nights, the bomber crews kept getting ready to launch, but each time were thwarted by the weather in Northern France. The specially-designed bombs were so heavy that the Lancaster bombers had to have them removed in rotation, to avoid damaging their suspension. Finally, the exhausted crews got word that the weather was clearing, and had ninety minutes to get ready to launch.

At that stage, Cheshire was summoned to a meeting. A group captain had arrived from headquarters, wanting to see him about a most important issue:

Cheshire saluted and the group captain looked a little severely at him. “Do you realise, Cheshire, that your squadron is last in the Group war savings scheme?” he said. “I’m very concerned and you’ve got to do something about it immediately”

- The Dam Busters by Paul Brickhill (1941)

Profiles in courage

It’s hard to exaggerate what a remarkable story Brickhill tells in his book about the work of 617 Squadron. On some folk level, even if only through Sunday afternoon film viewings and beer adverts, most of us know the story of the bouncing bombs developed by Barnes Wallis to attack German dams in the Ruhr. However, the story of the squadron’s contributions really only starts there.

By developing new bomb technology and ways to attack with precision, 617 Squadron transformed the military possibilities for the Allies. By bombing accurately enough to destroy strategic rail tunnels and bridges they prevented German troop reinforcements from arriving at the front. They harassed and sank the battleship Tirpitz. Their bombs broke through metres of reinforced concrete to destroy U-Boat pens. By flying pre-determined patterns in formation, dropping aluminium foil to confuse enemy radar, they played a big part in trying to deceive the Germans on the night of the D-Day landings.

This represented an extraordinary combination of technology and heroism. As well as the bouncing bombs, Barnes Wallis developed his earthquake bombs, whose fins would spin them up to penetrate deep into the ground before collapsing the earth above them on exploding. But, for all the accuracy of the bomb sights, it still required someone to fly at low level in a small plane to drop target flares for the bombers to aim at, and often that person was Leonard Cheshire.

Cheshire was a truly remarkable man: a fearsome warrior in wartime and a remarkable humanitarian in peacetime, recognised with the Victoria Cross and Order of Merit, and now even a serious candidate for beatification. He very much led 617 Squadron from the front, by developing new low-flying techniques to position the flares accurately and personally flying into great danger to drop them on a variety of precision raids.

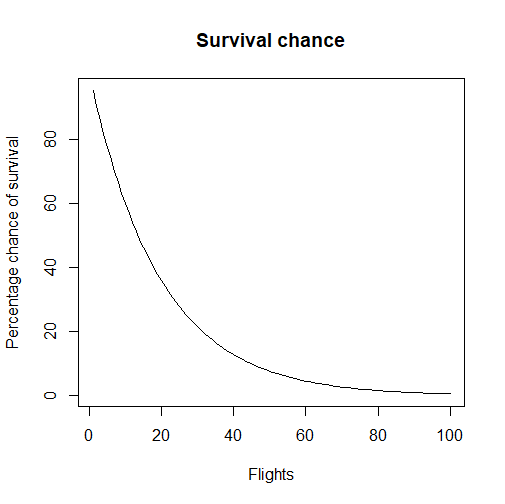

It’s reckoned that each bomber flying over Germany had a 5% chance of being shot down by fighter planes or anti-aircraft fire. It’s a simple calculation to see how this chance compounded over time:

If you flew 50 missions, you had perhaps an 8% chance of survival. If you flew 100, this would drop to 0.6%. Cheshire flew 100 missions. His Victoria Cross citation makes for astonishing reading, even for the description of one raid on Munich alone:

Wing Commander Cheshire’s cold and calculated acceptance of risks is exemplified by his conduct in an attack on Munich in April, 1944. This was an experimental attack to test out the new method of target marking at low level against a heavily-defended target situated deep in Reich territory. Munich was selected, at Wing Commander Cheshire’s request, because of the formidable nature of its light anti-aircraft and searchlight defences […] As he reached the target, flares were being released by our high-flying aircraft. He was illuminated from above and below. All guns within range opened fire on him. Diving to 700 feet, he dropped his markers with great precision and began to climb away. So blinding were the searchlights that he almost lost control. He then flew over the city at 1,000 feet to assess the accuracy of his work and direct other aircraft. His own was badly hit by shell fragments but he continued to fly over the target area until he was satisfied that he had done all in his power to ensure success.

But it wasn’t just Cheshire. Every member of the flying crew displayed courage which is unimaginable to most of us now, given the risks they faced: 56 out of 133 British and Commonwealth crew did not return from the original Dam Busters raid alone. But, as Brickhill recalls:

the aircrews were volunteers. They were where they wanted to be; not square pegs in round holes. They could leave whenever they wanted to, and none of them ever wanted to. They had pride in their special competence and purpose and were honoured for it.

Lessons learned

Without getting too cheesy and LinkedIn about it, it feels to me that the story of 617 Squadron tells us a lot about how teams succeed. The recipe seems deceptively simple: it was largely a case of recruiting great people, giving them what they needed, and then mostly staying out of their way. The story about the war savings seems awful, but it was probably the exception. But it’s something we should all remember: would the things we are asking people to do come in that category?

The personal eccentricities of the squadron that Brickhill describes1 were part of their identity, and probably helped them work better together. This actually feels like a common feature of high-performing teams, whether it’s Richard Feynman safe-cracking and bongo-playing his way through the Manhattan Project, or Alan Turing cycling to Bletchley Park in a gas mask because of hay fever and chaining his tea mug to the radiator. It’s possible that feeling the freedom to operate outside conventional standards helped Barnes Wallis to think of a bomb that could bounce on water, or Leonard Cheshire to break the rules on low-flying to develop his marking techniques.

In that sense, while a more conventional unit could perhaps have succeeded in the same way, the fact is that they didn’t. In the same way, remembering Churchill’s famous quote (“I know I told you to leave no stone unturned to get staff but I didn’t expect you to take me literally”) on visiting Bletchley, perhaps Enigma could have been cracked in other ways, but it wasn’t.

Jabs and jobs

This is also my feeling about the success of the UK’s COVID Vaccine Taskforce. The publication of Boris Johnson’s memoir has reignited the argument about whether the UK’s triumphant decision to run its own vaccine procurement process independently of the EU can be regarded as a Brexit benefit. A lot of people have been in “well actually” mode, pointing out that we could have gone our own way had we remained in the EU. But even the FactCheck issued by Channel 4 (not exactly fans of Brexit) grudgingly admits:

In October, the European Commission issued a “Communication” after EU countries agreed that no individual national regulator would move faster than the EMA.

It’s true that if Britain were still part of the trading bloc, we’d have been under political pressure to be part of that arrangement.

So my feeling is that while technically we could have operated independently while in the EU, realistically there’s no way that we would have. It was a mindset thing as much as anything else: if it was so obviously the right thing to go our own way regardless of Brexit, then how many #FBPE types were applauding the decision to do it at the time? Indeed, members of the Vaccine Taskforce suffered personal attacks from prominent people on the pro-EU side which didn’t exactly suggest support for their approach.

In her own book The Long Shot, vaccine tsar Kate Bingham describes how she moved from being a Remain voter with a position that “I was certainly not opposed to co-operating with the EU” (p89) via frustration at the fact that “For the better part of a month the procrastination continued” (p91) to “The European Commission seizing the reins and making it clear that it would operate on the basis of its own standard procedures crystallised the situation as totally unacceptable” (p92).

She goes on to quote the then Wellcome Trust Director Jeremy Farrar, who had previously argued for a pan-EU approach, as saying:

While I don’t like saying it, it was the best possible example of British exceptionalism approaching a challenge with a mixture of urgency, risk-taking and pragmatism. I am sure many in Europe wish the same approach had been brought to bear on behalf of the bloc.

While there wasn’t the same physical risk to the participants as Cheshire and 617 Squadron endured, it’s hard not to feel that the Vaccine Taskforce represented a similar spirit of talented people thinking outside the box. The EU’s bureaucratic requirements felt more like the “war savings” story than the actions of a forward-looking modern organisation.

But whether or not you agree with me on the Brexit and vaccine front, I hope that you can take the time to appreciate the courage of Leonard Cheshire and his men in their fight against evil. Have a good week!

Brickhill writes “Incompetence was never tolerated on the squadron but high spirits were, and the result was what Cochrane had aimed at: a unit of functional quality. He had long thought that one good performer was worth ten bad ones, and with 617 he proved it. The intriguing thing was that, so long as they were completely efficient, the rather punctilious Cochrane never unduly interfered with their somewhat spirited attitude towards life”

Good piece and something I’ll look into a bit more.

I’ve visited the blockhaus at Eperleques and the RAF sure put some big cracks in it!

I think the vaccine team did a stellar job and it actually felt like a war time level of urgency.

I just wish we’d apply same mentality to say the SMR programme. RR should be building them already!

As an observation, the quicker you do something, the cheaper it generally is. Finding consensus, scope changes and everyone having a veto are the killers of projects. You don’t have those ‘luxuries’ in war time.

Good Law project for me was just a political attack vessel. The fact they’ve stopped now says it all.

Whilst I feel a little bit nervous commenting on the stats of casualty rates on Bomber Command as you'll no more about statistics than I ever will, I feel the 5% casualty rate is a bit misleading, as whilst its correct overall, the more experienced you were the less likely you were to be killed (there were disproportionate numbers of crews shot down on their first few missions and the numbers also include training mission deaths, which again would be proportionately less experienced crews - eg disorientated by night flying) so Cheshire's actual chance of survival would be higher, as it wouldn't be a flat 5% across missions (though it was still extremely low and I'm not taking anything away from his bravery).