Climb every mountain

Gonna keep on tryin' til I reach my highest ground

Imagine you want to stand on the top of a hill. There’s an easy way to do that: wherever you are1 just look around and take a step in whichever direction takes you the steepest upwards. Keep doing that until there’s no direction that takes you higher. That was easy, and maybe it seems uninteresting. But actually it tells us something about teaching a computer to play chess, AI, and about the future of COVID variants.

We might describe our hill-climbing recipe as a “local optimization algorithm”. We have a quantity that we’d like to make big (our height above sea level), and we do it by taking decisions based on our immediate neighbourhood.

But the ambition to stand on the top of a hill is maybe a little bit weak. As I say, eventually you’ll reach a point where no step can take you higher, but you might just end up on top of some small hump of ground - whereas we might like to be more ambitious.

Suppose you were dropped into a country without a map, and told to stand on its highest piece of ground. All of a sudden, that’s a lot harder. It feels like our local rule won’t work any more: we might end up on a hillock or mound, but it feels unlikely that our path will lead us straight to the top of the absolute highest mountain, unless we are on a simple island with a single peak in the middle.

In some sense we need to explore the country more systematically. Instead of blindly just going upwards, we need to allow ourselves the freedom to backtrack, to go downhill sometimes, to move into new areas and explore other possibilities. Eventually, with enough time and patience we might find the high point, but you can imagine that the bumpier the terrain, the longer it might take.

Of course, this is a metaphor for something more interesting. We might genuinely be interested in climbing hills, but actually these days we’re more likely to set a computer doing it for us. We can think of situations with a whole bunch of possible states, where each one has a numerical value associated with it. For example, we could imagine a range of portfolios of stocks and shares, and we could find each portfolio’s value by adding up all their prices. It’s just like the idea that every spot on earth has a height above sea level associated with it.

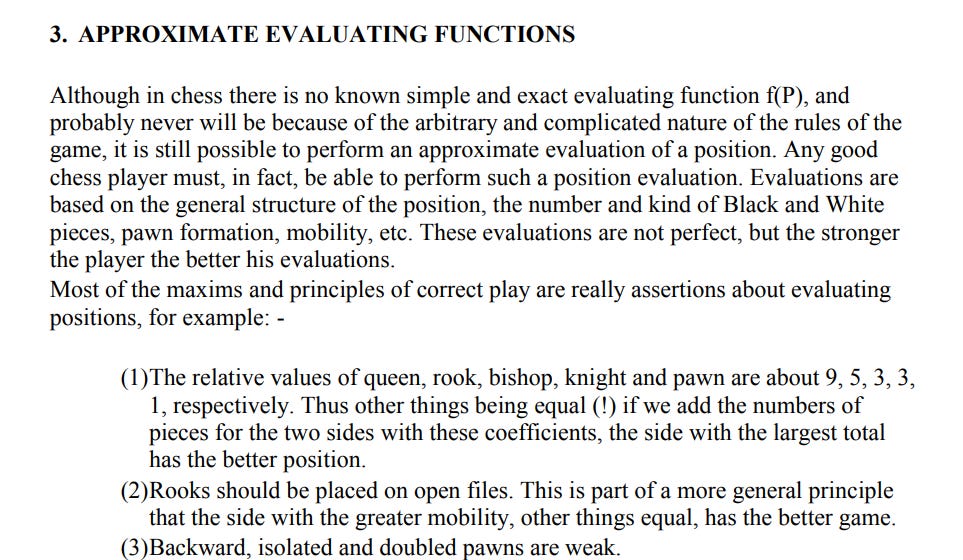

Indeed, the states and values can be quite abstract, but we could still think about asking a computer to find the highest value. All we really need is the idea of a “function” to keep score, as the visionary genius Claude Shannon realised as long ago as 1949.

Shannon had already made two huge contributions that shaped our modern world, in his 1938 Masters thesis (!) which argued that all computation could be performed by electrical circuits and his 1948 paper on information theory. But having done that, Shannon turned his attention to chess. Even at a time when computers were in their infancy, Shannon saw that you could teach one to play chess, and that all that you would need was a function to give the value of each position.

Once you had this, you can search through the possibilities with something like our local climbing rule. Which of my moves makes the value of my position highest? But then my opponent will respond. So if I move, my opponent takes their best option, and then I move again, which two-step configuration make the value the highest?

The bigger the computer, the further we can look into this chain of possibilities. The options will grow exponentially fast, so we might need to be smart and prune it (there’s no point examining all the possibilities after I throw away my Queen for no reason). But given a good enough function and enough time the computer can sort through the options and come up with something which feels like a strategy.

This idea, formulated by Shannon over 75 years ago, lies at the heart of any number of computer processes. It’s what lies at the heart of the reinforcement learning algorithms which drive much of modern AI. But there’s a sense in which it’s even older than that. In fact, instead of Shannon creating this principle, we might even argue that this principle created Shannon.

That is, it’s possible to think of the process of biological evolution as doing the same thing. Each time an organism reproduces and mutations are potentially introduced, we are making a move somewhere within the landscape of possibilities. And we don’t even need to know the value function, because Nature will keep track of that for us. The vast proportion of the mutations won’t confer any advantage, but the ones which do will survive and thrive, and so the population will skew towards those descendants.

Back on our hill-climbing analogy, we could imagine that one strategy to find the highest point would be to have ten children and send them out in random directions to explore. Then each child can do the same and so on, and soon enough we’ll get a sense of the whole landscape of the country, and one of our descendants will be close to the summit.

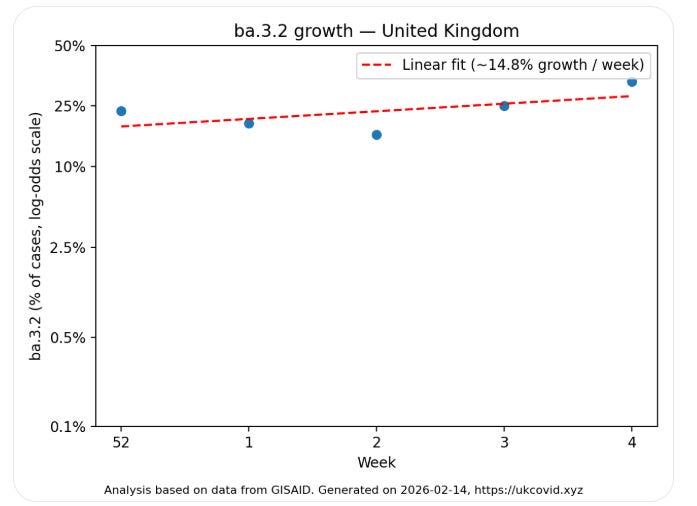

In fact, we’ve been watching something like this going on for the last six years in real time. There are a vast range of possible mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, most of which confer no advantage. But the ones which do can survive and thrive, and perhaps even outcompete the previous variants. We saw it relatively early on with the takeover of alpha in early 2021, followed by the arrival of delta a few months later, and the sweep of omicron towards the end of that year.

But since that omicron moment, not so much has changed. We’ve been stuck with the descendants of the original omicron since the start of 2022. It’s a bit like our search party taking a big step and discovering the Lake District. There’s been a whole new range of possibilities there and more heights to explore, but the relative gain by doing so has started to feel less each time, and COVID feels like less of a thing as a result.

If we check in with Dave’s site, we can see that the newest kid on the block (BA.3.2) has something like a 2% daily advantage over the other strains at the moment: that implies it might take over eventually, but that we might hardly notice it doing so in terms of a wave of hospital admissions.

Of course, all this might change. We might wake up tomorrow to find the new deadly pi variant has changed the game completely. But perhaps the longer it hasn’t happened, the more confident we might feel that it won’t?

We can appeal informally to the Lindy Effect, which suggests that the longer something has already been around, the longer it’s likely to last in future (bad news for Keir Starmer). And in the case of viral evolution you can see how this makes sense: if there’s a powerful completely different variant out there, why hasn’t evolution found it yet?

As I say, maybe it’s just a question of time and we’ll get there eventually. But in the last four years we can hypothesise there’ve been at least ten billion COVID infections worldwide. If we imagine that “each infected person carries an estimated 1 billion to 100 billion virions during peak infection”, we might be looking at something like a quadrillion (a one with eighteen zeroes) reproduction events in that time.

When you’ve bought that many lottery tickets and none of them have come up, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that the game might be rigged. It certainly doesn’t seem off the table (in the way that it did in the alpha-delta-omicron year of 2021) to imagine that COVID might have reached something like its final family form in omicron, even if it is likely to keep changing forever.

But as I say, who knows, so do feel free to tell me “this aged well” during the rho variant lockdown winter of 2028 … or not. And in the meantime, have a nice weekend and I hope you make it to the top of a hill somewhere!

Ok, maybe not Cambridge or Holland