Long COVID is a debilitating condition which has blighted the lives of millions of people around the world since 2020. I’ve often expressed scepticism of figures claimed for the percentage of COVID infections that lead to it nowadays, particularly ones which do not take proper account of reduced rates following reinfection and vaccination. However, that’s not to say that there is no risk at all, and as I wrote in my “Long COVID moonshot” piece earlier in the year:

Whatever the risks in the omicron era, it would be wrong to ignore the strong likelihood that there are hundreds of thousands of UK people (and presumably a comparable proportion of the population across many Western countries as a whole) who have suffered from serious forms of Long COVID for three years or more.

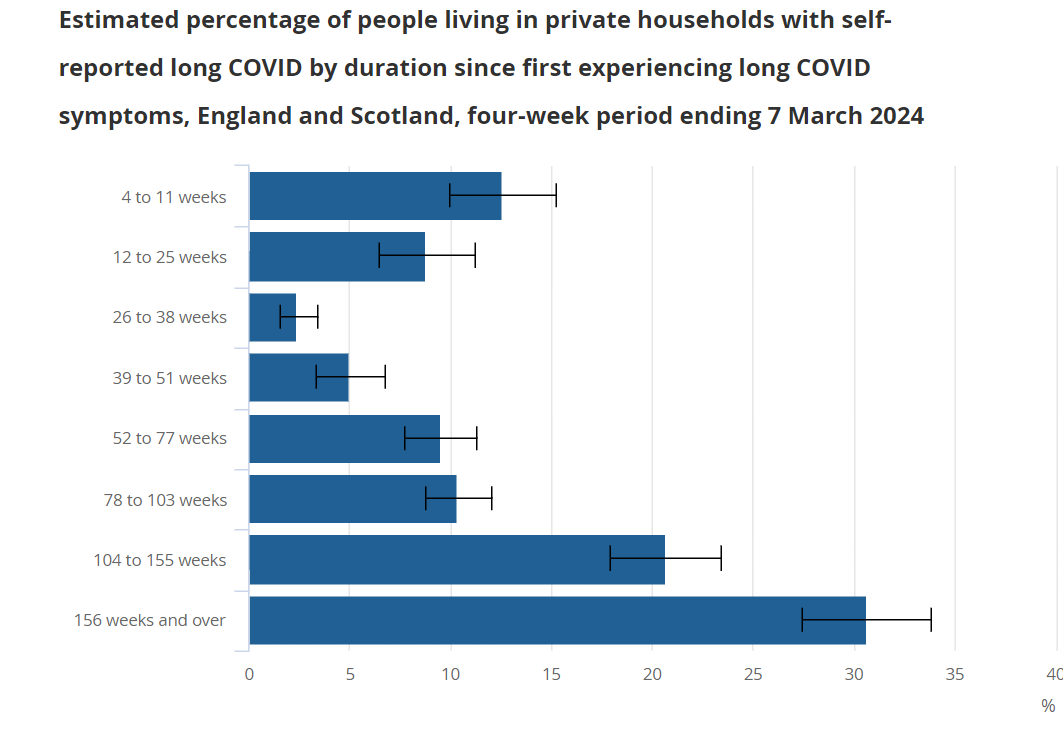

Indeed, while I only referred to a “strong likelihood” because of a lack of recent data1, it’s clear that this instinct was correct. Recently published data from the gold standard ONS COVID Infection Survey2 found 113k people in the UK whose activity was “limited a lot” by Long COVID and had been for two years or more, with a further 274k with activity “limited a little” throughout the same period. Based on this graph, it’s worse than that:

Three-fifths of those “2 years or more” people had actually been suffering for 3 years or longer, so ever since the pre-vaccination era. Overall, that’s something like the population of a city like Milton Keynes or Plymouth suffering serious health problems for that sustained period of time, with little prospect of improvement. It’s pretty shocking, and we don’t talk about it enough.

Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that it’s very easy to let your eyes glaze over at such large numbers. It’s sometimes hard to convert statistics into direct human impact, so I think it was good (albeit uncomfortable to read) that the Guardian recently published a couple of pieces on the human impact of Long COVID, focusing on the personal stories of people like Lucy and Toby.

This was important journalism, dealing with an under-reported problem. However, I have serious concerns about the latter piece in particular. Precisely because persistent Long COVID is such a devastating condition, I think we are obliged to be extremely careful when talking about possible treatments: we shouldn’t give false hope to sufferers, or advocate too strongly for experimental therapies for which the evidence base is currently uncertain.

The piece has been edited slightly now, but the original version contained the following statement:

Isabel has made improvements since receiving triple anticoagulant therapy to inhibit "microclots", which stop oxygen getting around the body as it should. This is believed to be one reason behind some of the symptoms of long Covid, including severe fatigue and pain.

I don’t believe that this statement accurately captured the state of the evidence, or fairly represented the controversy around this treatment. In the context of the piece it feels like clear advocacy for something which is at best unproven, and potentially even harmful. I think a national newspaper should be extremely careful in making such a case, and it should be done only after appropriate careful thought by specialist medical or scientific correspondents, rather than general features writers.

The reason for this is that medicine, and evaluating medical claims, is tricky. It’s very easy to convince yourself that a particular course of treatment is working, but human bodies are mysterious things. Conditions like Long COVID do sometimes just get better on their own (albeit not as fast as we’d like). The placebo effect can play strange tricks on us.

For this reason, we have developed the gold standard of a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Here, the test population is split in two, and a randomly chosen (and unknown to the doctor) subset of the group are given the proposed treatment, and the rest receive an appropriate placebo. Eventually the trial is unblinded (who got what treatment is revealed), and statistical tests are performed to see whether the treated group did better than the untreated, particularly by an extent that cannot be explained by random chance alone. Further, the trial protocol and statistical procedure should ideally be registered in advance to avoid possible moving of the goalposts by the researchers, even inadvertently.

This is how we tell the difference between medicine that works and medicine that doesn’t.3

It seems fair to say that the therapy advocated in this piece has not yet been entirely convincingly tested in this way. A recent paper by my Bristol colleague George Davey Smith and others reviews some of the evidence around this “microclot” theory in general, some of which also fed into a Cochrane Review4 (including some of the same authors) published in July 2023. This review was pretty stark:

1. The term 'microclots' is not the correct term for the particles being investigated in people with post-COVID-19 syndrome, as they are not clots. The term 'amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles' is more appropriate.

2. The evidence shows that amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles are found in healthy people and those with other diseases, so they are not unique to post-COVID-19 condition.

3. Patients should not receive plasmapheresis for this indication outside the context of a properly conducted placebo (dummy)-controlled randomized clinical trial (a type of study where participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more treatment groups).

I don’t believe that the Guardian piece properly reflected this controversy, and it’s fair to wonder whether its author was even aware of the Cochrane guidance. It seems there is reasonable doubt as to the role that such clots play in Long COVID, and hence to what extent the suggested treatment is appropriate.

In fact, it’s worse than that. It’s one thing to give people a treatment that may not work, but it’s much more serious if it has potentially significant side effects. The third point of the Cochrane Review alludes to this, by saying that these kinds of treatments should only be used as part of a clinical trial. The reasons for this seem pretty clear: affecting peoples’ blood is not a minor intervention.

has reported the outcome of a trial of this very therapy where things seem to have gone badly wrong for some patients at least:Out of 91 treated patients […] one sustained a gastrointestinal bleed necessitating hospitalization and a 2 unit blood transfusion. Three patients reported bleeding after they cut themselves, of whom one required medical attention.

I don’t believe that any reader of the Guardian article would have understood that this was a possible outcome of the treatment it advocated. In that sense, the whole tenor of the advice is highly concerning to me.

Indeed, it’s not entirely clear to me whether the recommendations of the Cochrane review are being followed in the procedures being reported in the article. You’ll recall that point 3 of the recommendations say that for now such treatment should only take place as part of a clinical trial.

While Dr Binita Kane (the physician in question) stated on Twitter that “a clinical trial is funded”, at the time of writing she has not responded to reasonable questions from medical journalist Deb Cohen5 about the details of such a trial. Nor has the indefatigable

been able to track down details of a trial being pre-registered as we might hope. At the very least, it would be reassuring to know that these protocols are being observed.This might all seem unfair. Of course, we all want to see treatments that work, and to be clear, I’m not even saying that this therapy definitely isn’t one of them. In fact it’s arguable that Long COVID is an umbrella term which potentially captures a range of conditions with different underlying causes, and that these sorts of treatments may play a role in helping with some of them. I just believe that in the circumstances we have to be very careful in the way that all this is reported, and I believe the Guardian report fell well short of doing that.

But the bottom line, and hopefully we can all agree on this, is that as I wrote before

we shouldn’t ignore the suffering of the long-haulers and should be funding further research into these types of conditions

I just think it’s important that we do this in the right way.

I think it’s important to be pedantic sometimes, or at least express the limitations of what we know. Sorry.

See Table 9 of the dataset associated with the survey for these numbers.

If you’re thinking this is Tim Minchin’s observation, I think it goes back to John Diamond in 2000. “There is really no such thing as alternative medicine, just medicine that works and medicine that doesn't”

Such reviews are the way in which the evidence in individual papers is synthesised into an overall view of the whole weight of thinking, and lead into recommendations for clinical practice.

A very interesting piece into a controversial subject.

I’ve had Covid at least 3 times and after each infection the cough has lasted for at least 10 weeks. After the second infection I’ve had an irregular heart beat (ectopics) so please take the next comment in good faith.

The pub talk is that long covid is the new bad back and doesn’t affect the self-employed so is there any data to support or refute that claim?

I’ve looked and can find certain sectors such as the civil service but no population wide demographic statistics on rates.

The similarities with CFS/ME seem extensive, including the extreme reactiveness of the pressure groups.