“Are you in pain, Frodo?' said Gandalf quietly as he rode by Frodo's side.

'Well, yes I am,' said Frodo. 'It is my shoulder. The wound aches, and the memory of darkness is heavy on me. It was a year ago today.'

'Alas! there are some wounds that cannot be wholly cured,' said Gandalf.

On Easter Saturday, it’s hard not to think back to previous years, and in particular to Easter Saturday of 2020. On that day, the world was collectively facing a new disease. Death figures were spiralling everywhere. In the UK, despite having been locked down for over two weeks, we reported 971 hospital deaths that day (and due to lack of testing, it’s likely that was an underestimate). We didn’t know if and when a vaccine would come, or how effective it would be. People’s lives were on hold, hospitals were under pressure, the news was unrelentingly grim. And yet, as we know now, even all that pain hadn’t come from sufficiently many infections to earn us a respite from a second wave in the winter.

It’s not like that now.

One of the strange things about COVID is that, compared with a war or similar traumatic events, there isn’t a well-defined end. There isn’t a signing of a peace treaty, but rather a slow fading away - perhaps each year the impact halves, and the rate of new harms exponentially decays.

Of course, none of this takes away the collective trauma that we all lived through. It doesn’t bring back the people who lost their lives, or help the people still suffering long-term health impacts (particularly from pre-vaccination waves) that I wrote about here. Nor does it compensate for the effects of those measures which were well-meaning but ineffective (or worse). But equally, there’s a danger in some quarters that by pretending that 2024 is anything like 2020, we underplay the horror of the past.

So while I think COVID now isn’t worth anything like the attention that I used to give it, it’s still not a bad thing to check in occasionally. In some sense, what follows is a sequel to this piece almost exactly six months ago, where I wrote:

by any reasonable comparisons we have to acknowledge that things aren’t like they were. 2023 isn’t as bad as 2022, which was nothing like as bad as 2021 or 2020. Of course, we still have the winter to get through, and while BA.2.86 has been growing slowly so far, there’s a likelihood it will pick up further mutations which will cause it to accelerate. But coming up on four years since this thing first emerged, it’s important that we remember that the situation is nothing like it used to be, and that it shouldn’t require any skullduggery with the data to convince yourself of that.

Overall, I think that’s aged fine. Indeed, the BA.2.86 variant did pick up more mutations to give JN.1. And while I wrote at the start of December that JN.1 likely had enough momentum to cause a future wave, by the 18th December I was suggesting that a drop-off in mixing would cause it to run out of steam, so the impact would be limited. I’m pretty happy that both of those calls were correct, at a time when other opinions were certainly available.

I haven’t written much on Substack since then in the way of COVID situation reports. To be honest, there’s not a lot to report, except for the sense that of course no news is good news. But to mark how different things are now, here are three reasons I think we can remain optimistic about the current and forthcoming situation:

Deaths

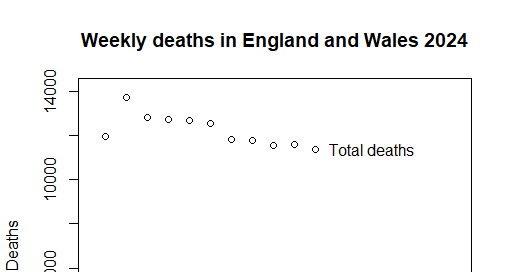

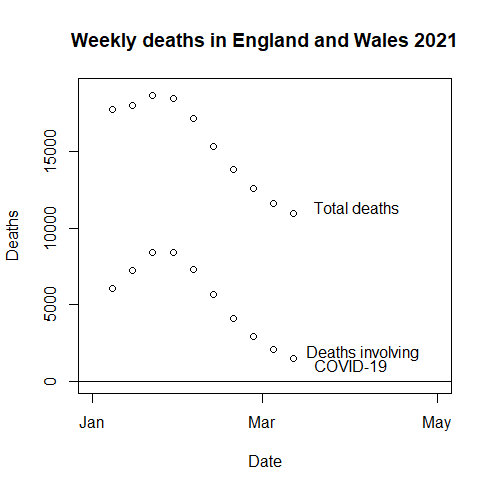

I shared the following graph on Twitter, which shows just how low COVID deaths are lately - both in absolute terms and as a fraction of total deaths.

Indeed, the most recent figure for deaths “due to” COVID-19 is 69 in England and Wales for a week, or back into single figures daily. This represents fewer than 1% of all deaths, despite referring to infections which probably took place in February when we might expect respiratory infections to be more severe. Compare this for the position in the corresponding months of 2021, and you’ll see that total COVID deaths were vastly higher then, both in absolute terms (I had to extend the y-axis up) and as a fraction of total deaths.

Indeed, it’s clear from the similar shape of the two curves on that graph that COVID deaths were a significant driver of the overall death numbers in 2021, leading to the significant excess deaths we saw at the time. In contrast, for all the claims from extremists of significant numbers of unreported deaths (either due to vaccine side-effects or the long-term effects of infections) we now are in a protracted period of negative excess deaths.

This is a somewhat tricky subject, because excess deaths must always be taken relative to a statistically-estimated baseline, and famously statisticians will disagree on almost any modelling question. However, even just looking at the expected death numbers by age (for example as plotted by the COVID actuaries) it seems clear that overall deaths are as essentially as low as they’ve ever been, and that the negative effects of the pandemic are no longer to be seen. That’s great!

Hospital data

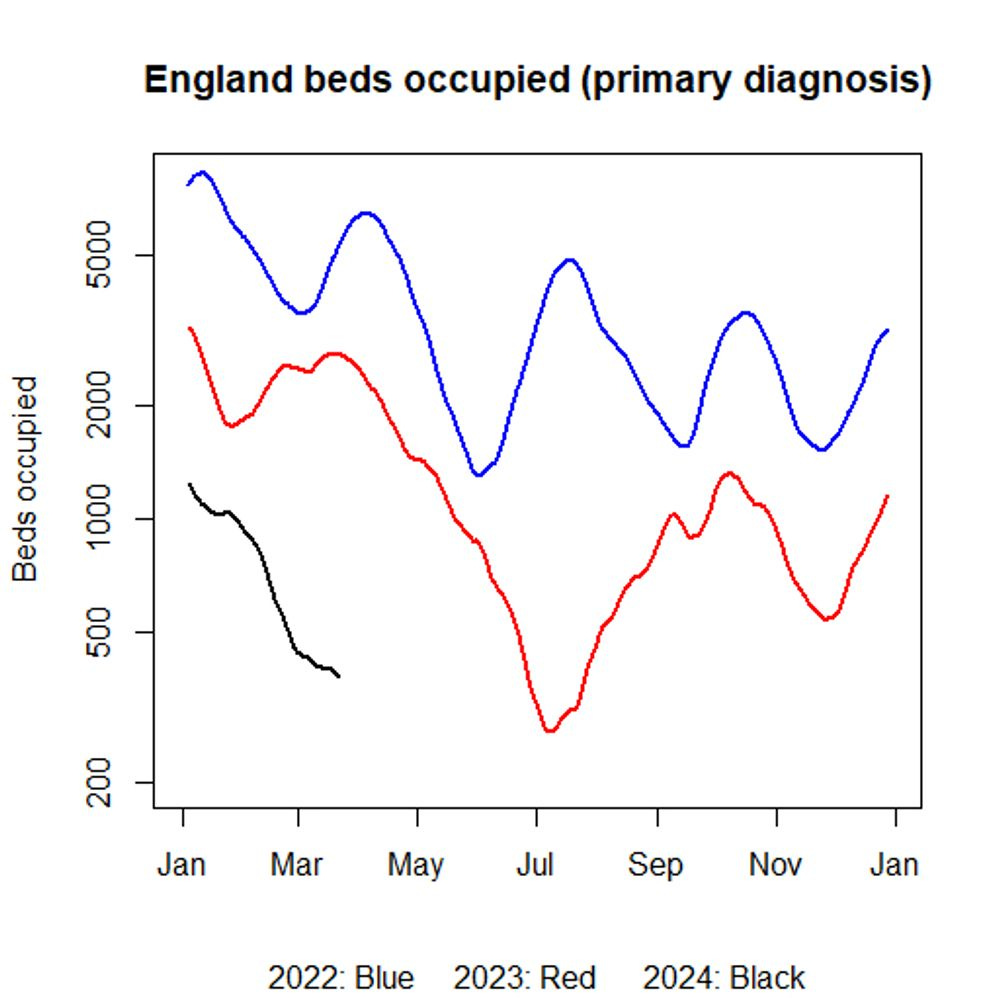

Back in that piece six months ago I made the claim (based on admissions and death data) that

so far every day of 2023 has been better than the corresponding day in 2022 for COVID in the UK

Of course, at that stage the year had three months left to run, and it wasn’t necessarily certain that this trend would continue through the autumn and winter wave. Well, the positive news is that not only did 2023 end up beating 2022 on this day-by-day basis, but so far 2024 has started better than 2023 did, in the same sense.

For example, this is a plot of primary diagnosis (“for COVID”) beds occupied1 in England. You’ll see the black line (2024) is below the red (2023) which was below the blue (2022). Immunity is a wonderful thing!

Indeed while last summer already saw very low levels of beds occupied (247 at the start of July 2023 was essentially the all-time low), we are down to 362 beds occupied by the start of April 2024, giving grounds for cautious optimism that even this record can be broken in the course of the next month or so.

Variants

As I mentioned above, the increase in admissions and deaths around Christmas time was caused by a combination of social mixing and the incoming JN.1 variant. Over the last couple of years, there’s been a fairly regular pattern of incoming omicron waves, with one taking over from the next in reasonably rapid succession. At one point in 2022, it looked like we might be in for a pattern of waves every three months. So it’s reasonable to assume that a new variant will come along and we will return to growth again at some stage.

Well, all I can say is that it hasn’t happened yet. I’ve not been keeping anything like as close an eye on it as I used to, but Dave McNally’s page is still live, and seems pretty encouraging to me. There are fewer sequenced cases than a few months ago, so the uncertainty is larger, but nonetheless, at a quick scan, the picture seems fairly quiet. Looking more widely, the WHO hasn’t added to their list of “Variants of Concern Lineages Under Monitoring” since JN.1 arrived.

JN.1 and its descendants make up about 95% of all UK sequenced cases at the moment, which means that the market share that anything else has is pretty limited. Skimming down Dave’s list, the non-JN.1 variant with the biggest share is something called XDK at about 3%. It doesn’t seem to have much of a growth advantage, but even if it did it wouldn’t reach the percentage share where it would cause growth for some time.

And the same is true of any other variant: even if a new Black Swan variant with a strong growth advantage came on the scene today, it would struggle to impact much on overall admissions numbers for the next couple of months or so. Further, having seen BA.2.86 and JN.1 burst on the scene with a large amount of hype about their numbers of mutations, but without either really leading to a major impact, it might be reasonable to be sceptical of how much damage future variants are likely to do. (Famous last words of course!).

Overall then, the COVID picture looks pretty healthy as we head towards summer. There may still be a few more bumps in the road to come, but this Easter seems incomparably better than the position four years ago, and so I hope you enjoy it.

Plug: the paperback edition of my book Numbercrunch is published on Thursday 11th April. It’s available from Amazon, and from elsewhere too. If you like my stuff on Substack, you’ll like the book.

Similar things are true for admissions, for example. The advantage of using “for COVID” beds is that they rely on doctors’ judgement to a greater extent, and so shouldn’t be so susceptible to changes in testing policy, giving people less reason to shout at me.

Thank you Oliver, I think this stuff is still enormously helpful.

I’m not sure death rates are actually the thing we need to be looking at to determine the impact of covid any more, given the lack of testing of non-hospitalised people with infections and the massive increase in long term illness. Plus I’d love to know how many of the deaths which are not directly labelled as covid, are heart/lung related and in people who have “recovered” from one or more covid infections. I worry that this gives a more positive impression than the situation warrants.